Module 4: Point of care ultrasound in first trimester abortion (POCUS)

7. Interpretation of ultrasound images

Click here to access a video explaining how to interpret ultrasound images

Grey Scale

An ultrasound image is made from reflected sound waves. Fluids reflect very little sound and so appear black, tissues reflect more sound and appear a lighter grey. Boundaries between tissues of different density can appear lighter still. It is these variations in grey which create the picture which represents the tissues scanned.

Artifacts

An artifact is any part of the ultrasound image that does not truly represent the structure it is viewing. Similar to audible sound waves, the environment though which ultrasound is transmitted can alter it causing echos, blocking sound or making it appear to be coming from a different source.

Artifacts typically occur when sound waves pass through different densities of tissues or hit the edge of a tissue type.

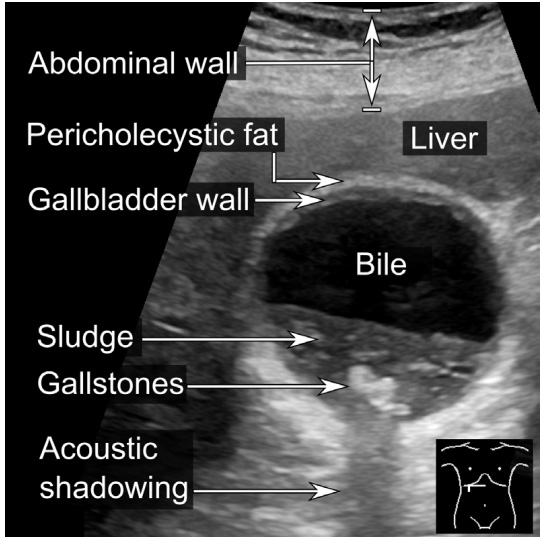

See figure 6 below for an example of how there is shadowing behind the gallbladder on ultrasound. This

occurs as sound waves are reflected back at the interface with the gallbladder and the quality of image behind this is degraded and shadowing artefact is produced.

It is important to recognise the possibility that the image seen could contain artifacts and therefore not truly represent the actual structure being scanned. By scanning through the structure in two different planes artifacts seen in one plane will be eliminated in the other, allowing clearer understanding of the imaging of the anatomy.

Figure 6. Ultrasound image of the gallbladder demonstrating different densities and shadowing.

Interpreting 2D images from a 3D uterus

One of the most difficult skills for someone new to ultrasound is learning how the 2-dimensional image on the screen relates to the 3-dimensional body part being scanned.

A simple way to visualise the ultrasound is by comparing the probe to a flashlight, where the beam coming out of it is in a single plane. The image on the screen is a representation of this "beam” as if viewed from the side. The very top of the image is the place where the transducer contacts the body and the image widens out as the beam passes into the body. The image ends at the deepest point that the beam has been set to penetrate.

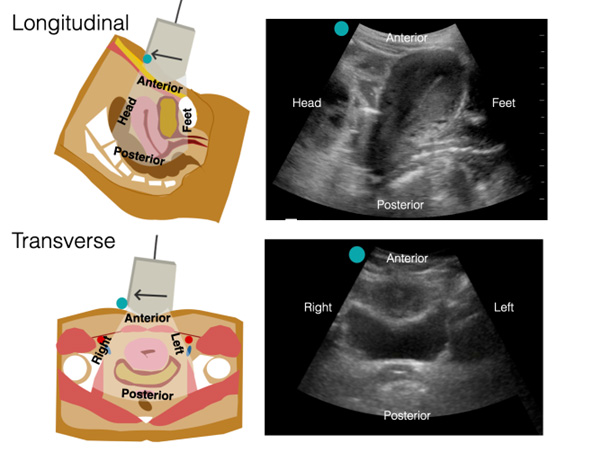

By tilting the probe from left to right and right back to left when scanning in the longitudinal plane (and from cranial to caudal in the transverse plane), you build up a group of 2-dimensional slices through the 3-dimensional structure (Figure 7). By doing this in real time you can develop a mental picture of the 3-dimensional image.

Figure 7. Visualising three-dimensional anotomical structures using the two-dimensional ultrasound image.

Images provided by Dr Sierra Beck.

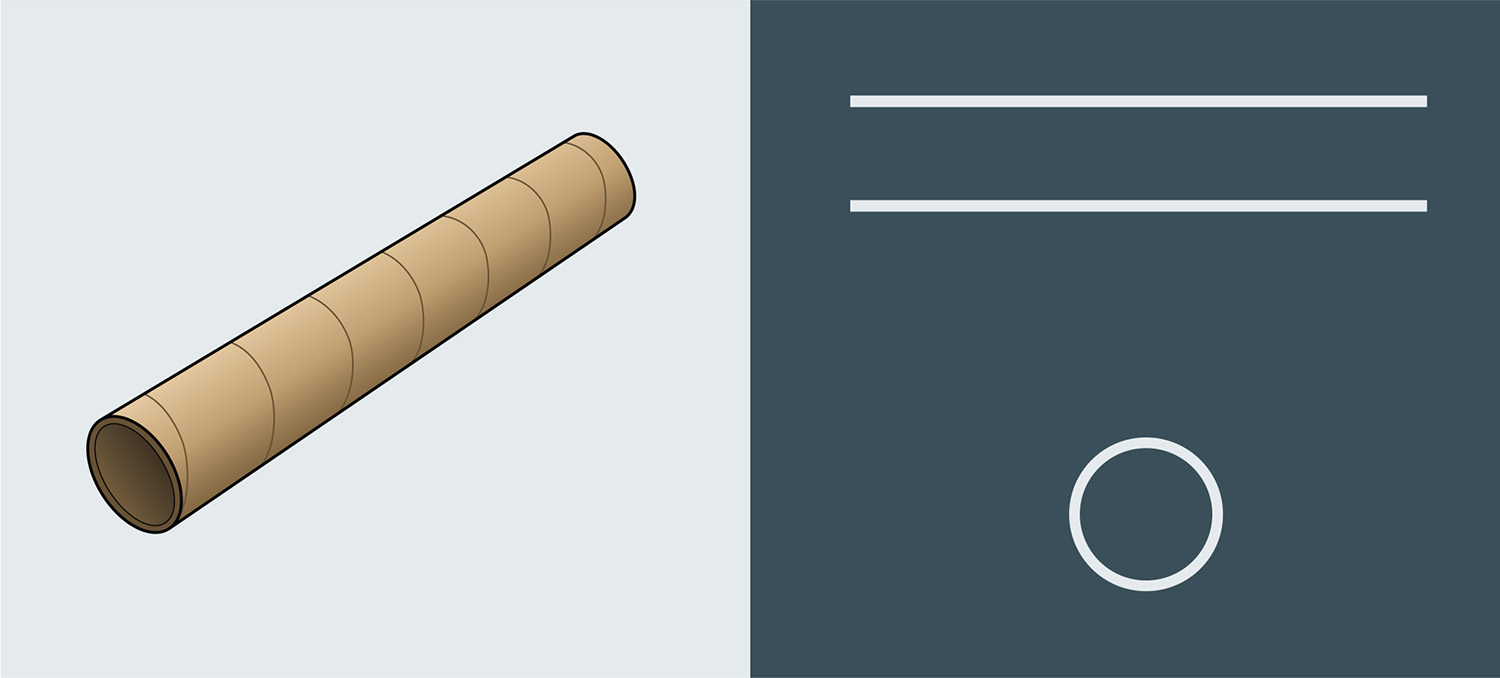

The images in Figure 8 show a cardboard tube as a 3-dimensional structure and how that structure would appear in a longitudinal and transverse 2-dimensional cut. The 2-dimensional images are quite different but combining them allows the ultrasonographer to create a mental image of the 3-dimensional structure. Once you have viewed the entire structure across both planes, you are in the position to freeze the single 2-dimensional image that is most appropriate. In the case of our scanning, this will either be the image that shows a structure or the one which shows the structure at its largest point for measuring purposes.

Figure 8. Example of how a 3-dimensional structure (left) appears in both a longitudinal or transverse 2-dimensional cut (right).

Is something inside the uterus or outside?

The importance of identifying the uterus and scanning all the way through the uterus (from side to side and top to bottom) before taking measurements cannot be stressed enough.

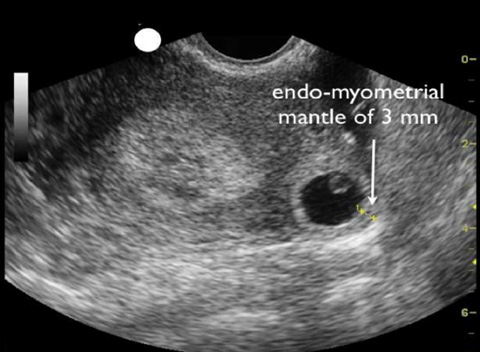

It is essential to make sure that, when viewing a gestational sac, that the sac is located entirely within the uterus surrounded by a thick rim of uterine muscle. The muscular wall (myometrium) of the uterus is seen in 360 degrees around the sac and continues to remain so as the scan passes through and out of the sac. Failure to do this could risk missing an interstitial ectopic pregnancy (Figure 9) – where only part of the sac is within the uterus, and part extends to the isthmus of the fallopian tube. In this situation the muscular structure of the womb will become very thin on the lateral extent of the scan.

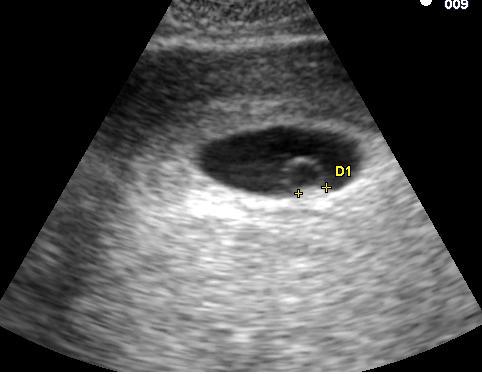

Figure 9. Ultrasound image showing an interstitial (cornual) ectopic pregnancy.

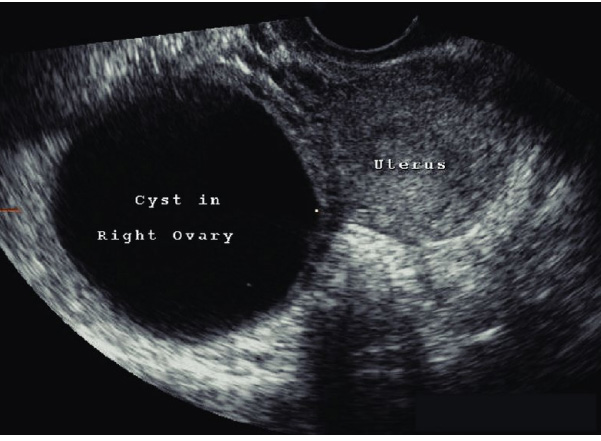

Similarly, novices to pelvic ultrasound sometimes make the mistake of thinking that an ovarian cyst (Figure 10) is a gestation sac by failing to confirm the presence of the muscular wall of the uterus around the fluid filled structure.

Figure 10. A simple ovarian cyst on the right side of the uterus.

Scanning early pregnancy

Before interpreting ultrasound images in early pregnancy, it is important to be clear about the structures that can be seen on early gestation scans.

The gestational sac is the fluid filled cavity that surrounds the embryo. In very early pregnancy it is formed by the chorionic cavity; as pregnancy progresses, the amniotic cavity expands to replace it. The gestational sac is the very first sign of pregnancy seen by ultrasound. The sac suggests an IUP but does not confirm it.

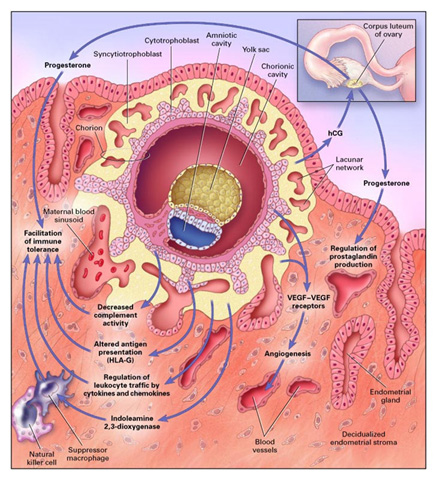

Figure 11 demonstrates an implanted embryo (approximately 14 days post conception) and the processes necessary for maintaining early pregnancy. As the embryo progresses, the large yolk sac develops and by around 5 to 6 weeks gestation is larger than the embryo. This is the second sign visible in early pregnancy on ultrasound, seen before the embryo, and is what confirms an IUP.

Figure 11. Implanted embryo approximately 14 days post conception.

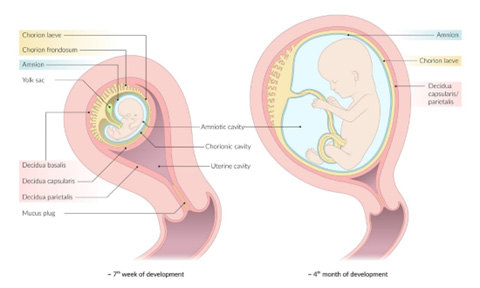

At approximately 6 weeks , the embryo fetal pole will be large enough to see on ultrasound. Around this time, both the embryo and yolk sac will be visible and as the pregnancy develops further the embryo becomes larger and the yolk sac smaller (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Diagram showing a foetus at 7 weeks gestation and second trimester gestation.

Distinguishing the gestation sac on ultrasound

The gestational sac is the very first sign of pregnancy on an ultrasound and appears as a fluid filled sac inside of the uterus.

For an example ultrasound image of a gestational sac, see Figure 1A at: https://www.contemporaryobgyn.net/view/an-imaging-approach-to-early-pregnancy-failure.

Whilst very suggestive of an early IUP, it is not conclusive proof. Similar images could be obtained with the presence of fluid inside of the uterus. One such cause is a pseudo sac, which involves fluid in the uterus associated with a tubal ectopic pregnancy.

For an example image of a pseudosac on ultrasound, see the image at: https://www.patientcareonline.com/view/pseudosac-ectopic-pregnancy

It is outside of scope for this point of care course to look at differentiating between a gestational sac and a pseudo sac. What is important is to be clear that the discovery of a fluid filled sac in the uterus in early pregnancy suggests early IUP but DOES NOT rule out ectopic pregnancy.

Measuring the gestational sac to estimate gestational age

As pregnancy advances, the gestational sac increases in size. The size of the sac can be used to calculate the gestational age of the pregnancy within an accuracy of 3 days prior to the ability to visualise the embryo.

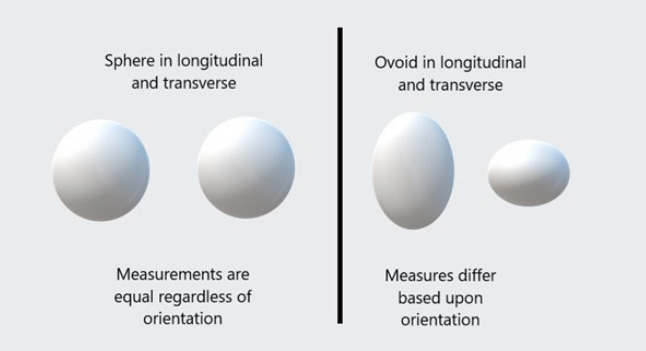

The shape of gestational sacs can vary, from spherical to ovoid.

Whilst a sphere will measure the same diameter in all directions, an ovoid may be much longer than it is wide or deep or vice versa. Therefore, taking a single measurement on an ovoid sac could lead to over or under estimation of its true size and therefore gestational age. The way around this is to calculate the Mean Sac Diameter (MSD). This is the average length from 3 measurements of the sac – top to bottom, side to side and front to back. Clinically, MSD is useful to correlate with LMP and improve confidence in gestational age estimation. To see examples on how to estimate MSD, see: https://obimages.net/free-chapter-normal-abnormal-first-trimester-exam/#Mean_Sac_Diameter_MSD

On a longitudinal 2D scan of the uterus and sac, the gestational sac can be measured from front to back and top to bottom. All that then remains is to measure side to side on the transverse scan. Most ultrasounds allow you to enter each measurement as you perform them. The average is then calculated, and the gestational age can be confirmed.

Clinically MSD is useful to correlate with LMP and improve confidence in gestational age estimation.

Distinguishing the yolk sac on ultrasound

As mentioned previously, the yolk sac is the next sign visible of early pregnancy on ultrasound after the gestational sac. Presence of the yolk sac allows confirmation that the pregnancy is intra-uterine. Visualisation of the yolk sac is all that is required, it does not need to be measured.

The yolk sac will appear as a smaller spherical sac within the gestational sac on ultrasound (Figure 13). It will be present before and remain present for several weeks after the embryo appears. Yolk sacs with no fetal pole are usually seen abdominally at 5 to 6 weeks gestation in an ongoing pregnancy.

Figure 13. A retroverted uterus with a gestational sac within the endometrial echo of the uterus and contains a yolk sac.

Determining Crown rump length (CRL) on ultrasound

The embryo is first visible at 6 to 7 weeks of gestation. When it first appears, it is smaller than the yolk sac (Figure 14).

As the embryo grows, its length increases faster than its width, meaning it is important to measure on the

longest axis. The measurement should be between the crown (top of the head) to the rump (NOT the lower

limbs). The CRL is the most accurate way to assess gestational age between 7 and 13 weeks when using transabdominal scanning.

Figure 14. Embryo when it first becomes visible on ultrasound.

As mentioned previously, when it first appears, the yolk sac is bigger than the embryo and often will be viewed adjacent to it (Figure 15). It is important to ensure that you only measure the CRL and not include the yolk sac.

Figure 15. Ultrasound image showing the CRL with callipers for measurement. Note that the yolk sac is adjacent to but not included in the measurement.

Image provided by Dr Sierra Beck.

As the length of the embryo increases it is important to measure along the longest axis (Figure 16).

Figure 16. Example of measuring the CRL along the longest axis on ultrasound.

Later in the first trimester, the embryo takes on an even more recognisable appearance (Figure 17). Care should be taken to ensure that the whole foetal head and rump are included when finding the long axis and the lower limbs are not included. Clinically, embryos with a CRL of less than 32 mm are suitable for early medical abortion (EMA; 32 mm correlates with approximate 10 weeks gestation).

Figure 17. Ultrasound image of embryo in late first trimester, including example CRL measurement (excluding lower limbs).

Distinguishing the foetal heart on ultrasound

After 7 weeks of gestation the foetal heart can be seen using an abdominal probe. It can be seen as a "flickering” within the otherwise still embryo.

Clinical note: do not diagnose/conclude that the pregnancy is not ongoing based on point of care ultrasound unless you have been specifically trained for this

Pregnancy of unknown Location

Pregnancy of unknown location (PUL) is defined as a positive pregnancy test but there are no signs of IUP or an extrauterine pregnancy via ultrasound.

This raises the possibility of the following differential diagnoses:

- Intra-uterine pregnancy too early or small to see

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Spontaneous miscarriage with ongoing positive pregnancy test

Management of pregnancy of unknown location is outside of the scope of this course. However, it is important to recognise that IUP should typically be seen on ultrasound with a transabdominal probe at serum βhCG levels above 3,500 and around 5 ½ weeks gestation.

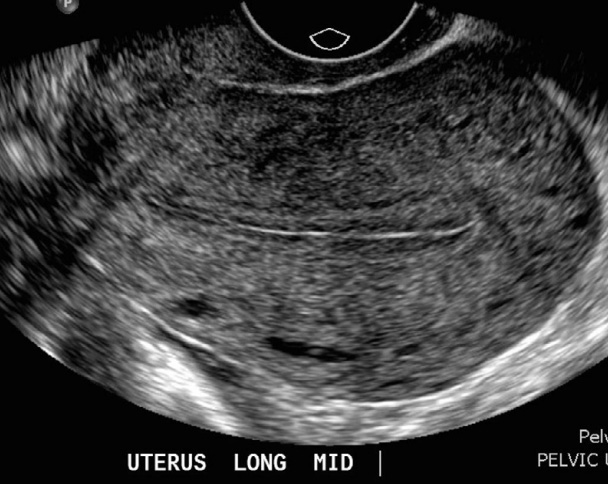

Distinguishing retained products of conception on ultrasound and differential diagnosis

Ultrasound is a useful tool in assessing retained products of conception. However, the ultrasound findings are rarely diagnostic alone and must be considered in conjunction with the clinical symptoms and signs, as well as information from other investigations (such as trends in serum βhCG). The empty uterus has a thin endometrial stripe (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Ultrasound image showing the endometrial stripe (visible as a thin echogenic line) at centre of uterus.

Case courtesy of Dr Alexandra Stanislavsky, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 30417

The transition in ultrasound findings associated with routine medical abortion does not involve a sudden change from IUP to a thin stripe. It involves a pathway between the two. Ultrasound scans performed soon after a miscarriage readily show the endometrium to be thickened as the uterus passes through the process of completion of the miscarriage. This should not be mistaken as retained products of conception requiring clinical management without suggestive symptoms and signs.

If retained products of conception is clinically suspected, an endometrial thickness greater than 10 mm is suggestive but does not confirm the diagnosis. An endometrial thickness of less than 10 mm makes retained products unlikely.

To measure endometrial thickness, take the thickest portion of the endometrium and measure perpendicular to

the myometrium from where the myometrium ends on one side to its start on the other (Figure 19). To review

images of retained products of conception, see: radiopaedia.org/articles/retained-products-of-conception

Figure 19. Example of how to measure endometrial thickness.

Distinguishing twin pregnancy on ultrasound

For the purposes of point of care ultrasound early pregnancy scanning, twin pregnancies can be diamniotic (two sacs) or monoamniotic (a single sac). Twins born from monoamniotic pregnancies are always identical, but diamniotic pregnancies can occur for identical or fraternal twins. Chorionicity is outside of scope for this course.

Both types of twin pregnancies should be visible by 7 weeks of gestation. Diamniotic pregnancies are seen at early gestations as the presence of two gestation sacs can be seen without the need for the embryo to have developed large enough to be visible (Figure 20). Monoamniotic twins show two embryos within a single sac, so appear slightly later in scanning (Figure 21).

Figure 20. Ultrasound image of diamniotic twins at 8 weeks

Figure 21.Ultrasound image of monoamniotic twins at 15 weeks.

When things don't look right

Point of care ultrasound is based on the principle of answering a simple clinical question (such as “what is the gestational age?”); it is not intended to be a full diagnostic scan. However, there will be times you come across something that does not look right but is outside of the scope of this point of care ultrasound training:

1. Ectopic pregnancy

It is not within scope of this training to diagnose an ectopic pregnancy (or its effects) on ultrasound. However, a cystic structure seen outside of the uterus, when there is no intrauterine pregnancy seen, should raise suspicion. Ultrasound findings should always be integrated with additional symptoms, signs and clinical judgment.

2. Ovarian cysts

Functional ovarian cysts are common in early pregnancy, pathological ovarian cysts less so. Direct visualisation of the ovaries is outside of the scope of this training. However, there will be a time when the clinician performing point of care ultrasound views a cystic structure outside of the uterus. Scan through cystic structures in both planes to ascertain if they are intra or extra-uterine. Should a cystic structure be seen outside of the uterus, consider referring for clinical assessment and radiology performed ultrasound.

3. Intrauterine devices

Intra-uterine devices (IUDs) can be seen on ultrasound as a bright linear structures within the endometrial canal on longitudinal imaging (Figure 22).

Figure 22. Copper IUD visualised on ultrasound.

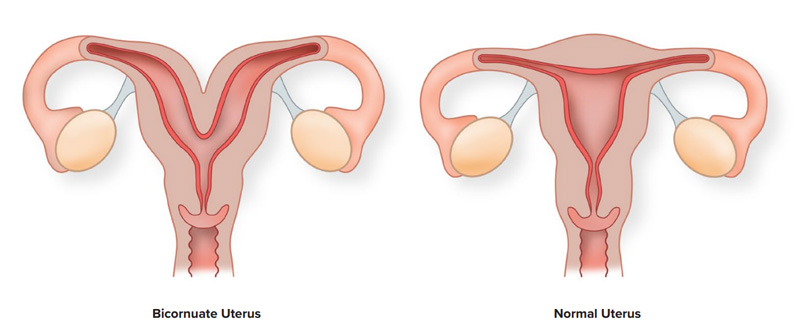

4. Bicornuate uterus

Whilst the normal uterus is shaped like an upside-down pear, the morphology of bicornuate uterus can be anything from heart shaped to two separate uterus horns (Figure 23). It is most noticeable in the transverse image when scanning near the fundus where the endometrial cavity splits into two separate horns (Figure 24).

Figure 23. Diagram comparing a bicornuate (left) and normal (right) uterus.

Figure 24. Transvaginal ultrasound showing a cross-section of a bicornuate uterus, with two cavities ("horns") to the left and right, respectively. The cavity to the right contains a gestational sac.

What to do when you don't know

If you come across the above findings or anything you are unsure of, consider the urgency with which a patient needs to be referred for a radiology performed ultrasound or to a specialist clinical review.