Module 1: Consultation – communication and decision making

4. Medical history and establishing gestation and location of pregnancy

Focused medical history: contraindications and complication risks

The pregnancy should be confirmed by urine or serum testing, and a focused medical history needs to be taken to identify any contraindications or risk factors for abortion and to aid in subsequent contraceptive choice.

Absolute contraindications to EMA include:

- Allergy to mifepristone or misoprostol

- Adrenal failure

- Poorly controlled severe asthma

- Steroid dependency

- Hereditary porphyria

- Intrauterine contraception (IUC) in situ – it is okay to proceed if this is removed

- Known or suspected ectopic pregnancy

Relative contraindications to EMA include:

- Greater than 70 days of pregnancy

- Severe anaemia

- Serious or unstable health conditions such as ischaemic heart disease, uncontrolled epilepsy, renal failure, or hepatic failure

- A known bleeding disorder or taking anticoagulant medicines

The New Zealand Aotearoa Abortion Clinical Guideline recommends that an EMA can be provided for pregnancies up to 10 weeks (70 days). N.B. mifepristone is at present (2022) licensed in New Zealand for up to 63 days. The unapproved use of mifepristone is discussed in greater detail in Module 2

Of patients having EMA, 1% will have heavy bleeding which can be unpredictable in terms of timing. It may be safer for a patient with severe anaemia, an unstable health condition or a bleeding disorder to have surgical management or an EMA in a hospital setting. Haemoglobin testing is not routinely recommended but is recommended for people with a medical history of anaemia including postpartum haemorrhage or heavy menstrual bleeding or current symptoms.

While the risk of heavy bleeding and cervical shock following an EMA are low, this increases with gestational age. It is essential to ensure people having an EMA in the community are safe and able to access emergency health care facilities if required. Determining whether this is the case needs to form a part of each individual’s consultation process. If there are social or practical barriers to emergency care access, then an at home EMA is not appropriate, and other options (e.g. early surgical abortion, or EMA in a different setting) should be offered as part of the shared decision-making process.

Examples of potential barriers to emergency care access:

- No reliable telephone access, or a limited ability to communicate with an emergency health service (e.g. language barriers)

- No transport or no adult companion at home

- Physical distance – e.g. being further than one hour from the nearest emergency health service.

Medical history and surgical abortion

There are no absolute contraindications to surgical abortion and conditions that increase the risk are often considered contraindications to EMA. People seeking an abortion who have a complicated medical or surgical history may be recommended to have a surgical abortion in a hospital rather than community service. Management of complex medical conditions and surgical abortion are covered in Module 3.

Establishing gestation and location of pregnancy

New Zealand Aotearoa Abortion Clinical Guideline 2021, recommendation 1.3.3 is: “Determine gestational age of the pregnancy by clinical means (history including last menstrual period, with or without examination) or ultrasound scan”

Recommendation 1.3.7 is: "Recommend selective ultrasound prior to first-trimester abortion if there is uncertainty about gestational age by clinical means, or if there are symptoms or signs suspicious for ectopic pregnancy"

Recommendation 1.3.10 is: "Perform relevant Physical examination as indicated"

Normal early intrauterine pregnancy (IUP)

It is important to understand normal and abnormal early pregnancy development to ensure that abortion care is provided safely. Bleeding and/or pain in early pregnancy are not normal and need further evaluation. abortion providers should be aware of early pregnancy assessment services available for people with early pregnancy complications in their community and have referral systems to them.

Structures generally develop in the following predictable sequence during early pregnancy:

- Gestational sac

- Double decidual reaction

- Yolk sac (intrauterine gestational sac with yolk sac confirms early IUP)

- Embryo

- Embryonic cardiac activity

The timing of structure development is also predictable:

- Gestational sac: Visible at approximately 5 weeks gestation, ± 4 days

- Yolk sac: Visible at approximately 5 ½ weeks gestation, ± 4 days.

- Embryo and cardiac activity: Visible at approximately 6 weeks gestation, ± 4 days

Some key points to remember about intrauterine pregnancy include:

- If a fertilised egg implants in the endometrium, pregnancy hormones sustain the pregnancy

- A gestational sac is the first ultrasound evidence of pregnancy and is visible by 5 weeks

- The yolk sac is the first ultrasound finding that confirms an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP); it typically appears at 5½ weeks gestation

- The yolk sac partially nourishes the developing embryo

- Before an embryo is visible, the mean sac diameter (MSD) can support estimating gestational age by LMP/ bimanual examination

- The embryo follows a predictable path of development and can be used to date a pregnancy based on its size; it appears around 6 weeks

- Once an embryo is visible, the crown-rump length (CRL) should be used to calculate gestational age (accuracy +/– four days)

For further information on ultrasound in pregnancy, see: The New Zealand Obstetric Ultrasound Guidelines, 2019

Last menstrual period (LMP)

Providers need to take a standard menstrual history focusing on the first day of the patient’s last menstrual period (LMP), including:

- How sure they are of the date

- If it was a normal menses for them

- Any recent use of hormonal contraception (including pill, injection, intrauterine, implant)

- If their menstrual cycles are regular and if so, the average length of the cycle

In studies of people seeking first trimester abortion who were reasonably certain of their LMP, self-reported gestational age correlated closely to ultrasound gestational age.

Physical examination

A bimanual examination helps to estimate the gestational age – the size of the uterus increases by

approximately one cm for each week from four weeks to 12 weeks’ gestation. A study of pelvic examination to

assess gestation agreed with ultrasound for 92% of experienced providers; however it should be noted that

the estimation of gestational age can be less accurate in the presence of obesity

If the gestational age estimates based on the menstrual history and pelvic examination are consistent, and the person has no symptoms of pain or bleeding, then proceed with the EMA or surgical abortion. A systematic review found no evidence that routine ultrasound improved safety or efficacy compared with other diagnostic methods. If there are any concerns, however, arrange for an ultrasound scan.

The roles of ultrasound (US) in early pregnancy are to determine the pregnancy location (to confirm an IUP), confirm the number (single or multiple), document gestational age, and if appropriate, to detect fetal cardiac activity. Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) with a handheld device can achieve these outcomes via an abdominal scan. However, a transvaginal ultrasound may need to be performed if an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is not identified on a transabdominal scan. For more information on this see Module 4.

If providing an abortion via telehealth, see section 2 on telehealth.

Interpretation of βhCG

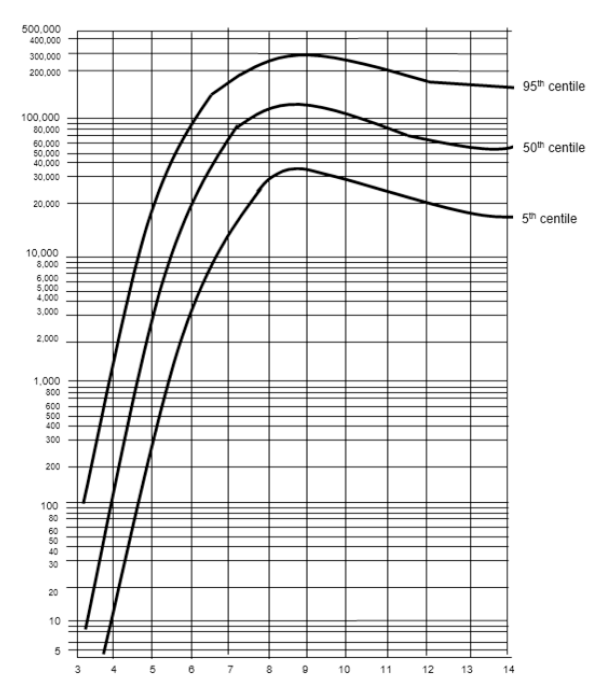

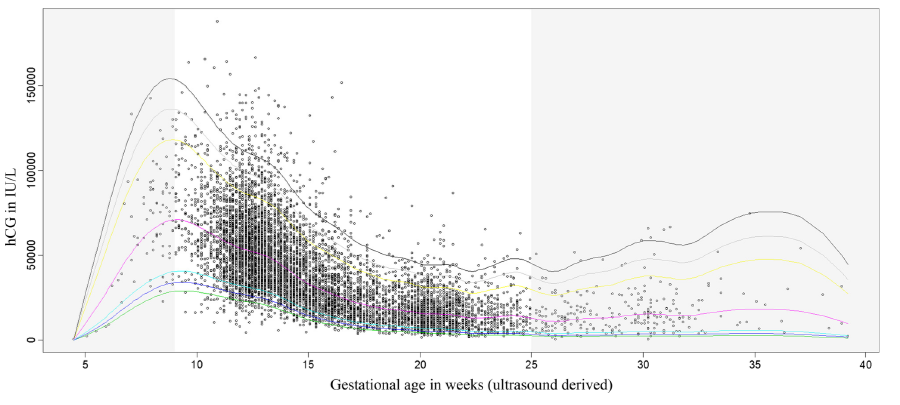

βhCG must be correlated with ultrasound appearances in cases where an ultrasound scan has been completed – refer to local clinical guidelines or for more information on obstetric ultrasound see this link. If the βhCG is significantly higher than anticipated, consider the possibly of a molar pregnancy and manage as per standard guidelines for gestational trophoblastic disease. βhCG alone should not be used for dating and must be corelated with the LMP, clinical examination and/or the ultrasound scan findings. Figure 1 and 2 show total hCG levels in the first trimester, and over the entire pregnancy demonstrating the drop in second and third trimester to levels found in early first trimester.

Figure 1. First trimester βhCG levels. Source: New Zealand Obstetric Ultrasound Guidelines

Figure 2. Centile curves for total hCG (not βhCG) during an entire pregnancy. Source: Korevaar T.I.M., Steegers E.A.P., De Rijke Y.B., et al. Reference ranges and determinants of total hCG levels during pregnancy: the Generation R Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30(9):1057–66. Available here

Interpretation of ultrasound

Yolk sac

The presence of a yolk sac within the intrauterine gestational sac confirms an intrauterine pregnancy and essentially excludes ectopic pregnancy. Heterotopic pregnancy, where an IUP and an extrauterine pregnancy coexist, is very rare but should be considered if there are suggestive ultrasound features, particularly in the setting of assisted reproductive technology.

Crown-rump length (CRL)

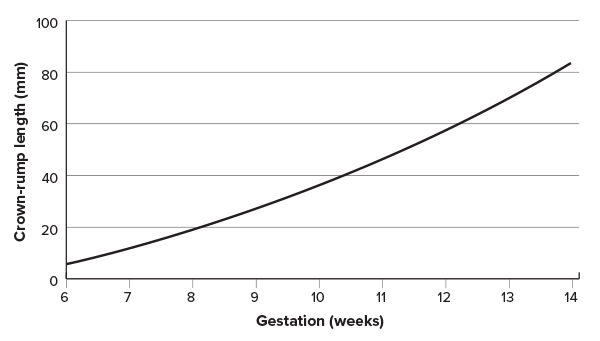

Growth is approximately 1.2mm per day but may be less in a normally developing pregnancy. Interval growth of CRL alone should not be used as a determinant of pregnancy loss. Figure 3 shows the rate of increase in CRL over the first 14 weeks of pregnancy.

Figure 3. Crown-rump length during early pregnancy. Source: Westerway SC, Davison A, Cowell S. 2000. Ultrasonic fetal measurements: new Australian standards for the new millennium. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 40(3): 297–302. Available here

Cardiac activity

Embryonic cardiac activity (pulsatility) should always be visualised with a CRL ≥7 mm. A slow embryonic heart rate of <80 bpm may suggest a guarded prognosis for the pregnancy. Suggest a follow-up ultrasound scan if clinically appropriate.

Ultrasound and miscarriage diagnosis

Information on the diagnosis of early pregnancy loss by ultrasound are available in the “Early pregnancy loss” section of the New

Zealand Obstetric Ultrasound Guidelines, and further detail on this is provided in Module 4. It is very

important not to misdiagnose miscarriage for people with a wanted pregnancy. However, there is no need to confirm an “ongoing

pregnancy” prior to proceeding to an abortion.

Pregnancy of unknown location

Pregnancy of unknown location (PUL) is defined as the situation when the pregnancy test is positive but there are no signs of intrauterine pregnancy nor is an extrauterine pregnancy visible on transvaginal ultrasonography.

The definition of ectopic pregnancy is when a fertilised ovum implants outside of the uterine cavity. Approximately 1% of known pregnancies are ectopic. The vast majority of ectopic pregnancies are located in the fallopian tube. The aetiology of ectopic pregnancy includes the following factors:

- Obstruction or dysfunction of the tubal transport mechanisms

- An intrinsic abnormality of the fertilised ovum

- Conception late in cycle

- Transmigration of the fertilised ovum to contralateral tube

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include:

- A previous ectopic pregnancy (increases the risk 10 times)

- A history of pelvic infection (e.g. STI, PID, endometritis)

- Intrauterine contraception in situ

- Adhesions from previous pelvic surgery or endometriosis

However, in 50% of ectopic pregnancies, no risk factors are identified. Typical symptoms include:

- Amenorrhea with PV spotting or bleeding (the most common presentation)

- Pelvic pain, usually one-sided

- Other pregnancy symptoms

- If ruptured, then symptoms of shock (e.g. pallor, sweating, fainting, increasing pain, shoulder tip pain)

The characteristic signs of ectopic pregnancy include:

- Tenderness or signs of peritonism on abdominal examination

- Cervical motion tenderness (CMT) on pelvic examination

- Adnexal tenderness or mass

- If ruptured, then signs of shock and an acute abdomen

The diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy is usually made with a strong index of suspicion based on the presentation and clinical findings, serial serum βhCG and a confirmatory pelvic ultrasound scan provided there are no symptoms or signs of shock. It is expected that an intrauterine gestational sac will be seen using trans- vaginal ultrasound (TVUS) at a βhCG level of 1500–2000 IU/L. If this is not present, then suspect an ectopic and ensure follow-up and appropriate management.

Management depends upon whether the patient is haemodynamically stable. If the patient is haemodynamically unstable, or there is significant concern about the degree of pain or bleeding, refer directly to secondary care (emergency department). If the patient is stable, then it may be appropriate to refer to an early pregnancy assessment service for ultrasound diagnosis and specialist management.

Miscarriage

Suspect miscarriage in patients presenting with bleeding or other symptoms and signs of early pregnancy complications who have pain or a pregnancy of six weeks gestation or more or a pregnancy of uncertain gestation.

Management:

- If haemodynamically unstable, or there is significant concern about the degree of pain or bleeding, refer directly to secondary care; or

- Refer to an early pregnancy assessment service for ultrasound diagnosis and specialist management.

Inform the patient that the diagnosis of miscarriage using one ultrasound scan cannot be guaranteed to be 100% accurate and there is a small chance that the diagnosis may be incorrect, particularly at very early gestational ages.

In the absence of a previous scan confirming an intrauterine pregnancy, always be aware of the possibility of a pregnancy of unknown location.

Further reading and resources:

- For further information on the diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage, see NICE Guideline 126: “Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management”

- To read more about ectopic pregnancy, see Richardson A, Gallos I, Dobson S, Campbell BK, Coomarasamy A, Raine-Fenning N. (2016). Accuracy of first-trimester ultrasound in diagnosis of tubal ectopic pregnancy in the absence of an obvious extrauterine embryo: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obs Gynecol 2016;47:28–37. Available here

- To read more about how to determine nonviability, see Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, et al. (2013). Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1443–51. Available here

- For a video on decision counselling following a positive pregnancy test results, click here