Key practice points:

- Recurrent or severe respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are risk factors for bronchiectasis. Prevention and prompt

treatment of wet cough, the cardinal symptom of a persistent RTI, in high-risk children can help to stop

this process.

- Treat wet cough with a 14-day course of antibiotics. Guidelines recommend initiating treatment for cough of more

than four weeks duration; consider a lower threshold for initiating antibiotic treatment in children at high risk of

bronchiectasis.

- Antibiotic choice for persistent wet cough should ideally be guided by susceptibility testing. Suitable choices for

empiric treatment include amoxicillin or trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole, as guided by local resistance patterns.

- Implement strategies to prevent recurrent episodes of wet cough, i.e. encouraging a smoke-free home, good hygiene

practices, keeping up-to-date with childhood immunisations, encouraging influenza and additional pneumococcal vaccinations

(these may be funded for some children). Refer to local housing services (e.g. for insulation, curtains, housing assistance)

if available and the family is eligible.

- Early diagnosis of bronchiectasis and prompt treatment of exacerbations can help prevent its progression, and may

allow reversal in some cases. Refer children with suspected bronchiectasis for paediatric assessment.

- Antibiotics and chest physiotherapy are the mainstays of managing bronchiectasis exacerbations. Ensure each child

has a bronchiectasis action plan and that the child’s parents or other caregivers understand when to seek medical advice

for an exacerbation.

Bronchiectasis is a chronic lung disease characterised by bronchial dilation and chronic inflammation, with chronic

wet or productive cough.* An initial trigger (see below) results in bronchial dilation, which in turn impairs mucociliary

clearance, facilitating recurrent cycles of infection and inflammation that lead to progressive remodelling and scarring

of the bronchial walls. Without treatment, bronchiectasis can lead to impaired lung function, respiratory failure and

in very severe cases can rarely lead to death in early adulthood.

Although bronchiectasis can occur at any age, this article focuses on prevention and management in children. Māori and

Pacific children and those from lower socioeconomic communities have the highest rates of bronchiectasis; contributing

factors include increased risks of overcrowding and infection transmission, cold and damp housing, smoking and reduced

access to healthcare (see: “The burden of bronchiectasis in New Zealand children”).1, 2

For further information on diagnosing bronchiectasis in adults, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2012/September/bronchiectasis.aspx

* A productive cough is associated with sputum expectoration. Younger children cannot expectorate and sputum is usually

swallowed or vomited; cough in this group is described as “wet”.3 Purulent sputum is a feature of bronchiectasis.3

The burden of bronchiectasis in New Zealand children

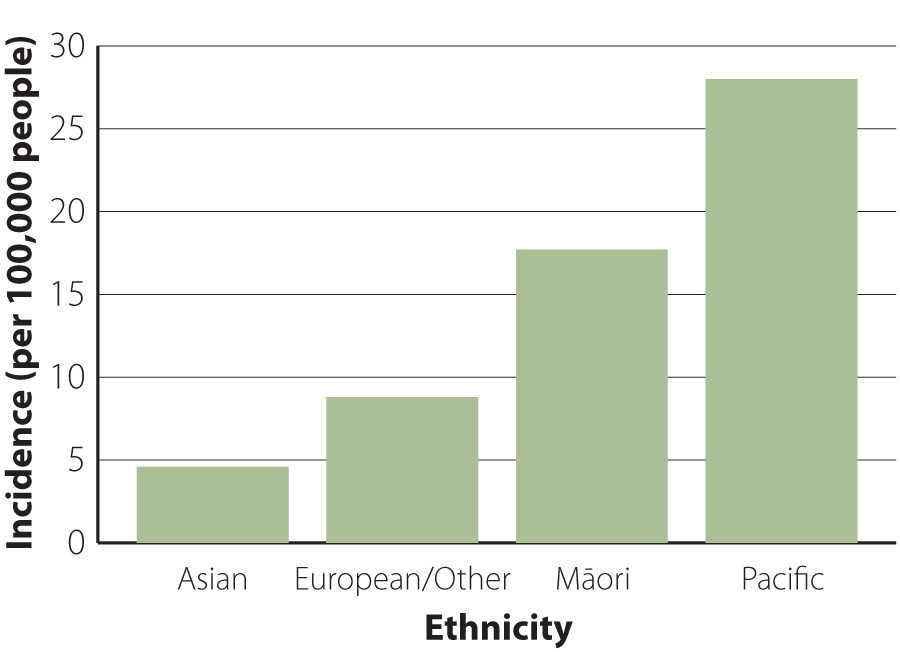

In 2017, there were 123 new cases of severe bronchiectasis (defined as hospitalisation with bronchiectasis as a primary or secondary diagnosis) in New Zealand children

aged < 15 years.1 The incidence rate was three times higher in Pacific children and two times higher in Māori children than those of European/Other

ethnicities (Figure 1). The incidence of hospitalisation increased with socioeconomic deprivation, such that the incidence in the most deprived quintile

was nearly 2.5 times higher than the least deprived quintile.1

Figure 1. The bronchiectasis incidence rate (per 100,000) in New Zealand

children aged < 15 years in 2017, by ethnicity.1

What causes bronchiectasis?

There are various causes of bronchiectasis, many of which are preventable. Recurrent or severe respiratory tract infections

(RTIs), e.g. pneumonia (both bacterial and viral), adenovirus, measles, pertussis and tuberculosis can cause bronchiectasis

in children.4 Hospital admission for a lower RTI (pneumonia or severe bronchiolitis) in the first two years

of life is a risk factor for a future bronchiectasis diagnosis.2 Some children develop protracted bacterial

bronchitis following a RTI; this is a persistent bacterial infection of the airways, resulting in chronic wet cough that

responds to prolonged antibiotic treatment. It is thought that protracted bacterial bronchitis is a step in the development

of bronchiectasis for many children, but with appropriate management it can be a reversible cause.5, 6

Other causes of bronchiectasis include genetic disorders (e.g. cystic fibrosis), immune deficiency or undiagnosed foreign

body aspiration.4 In cases where the cause of bronchiectasis is unknown it is presumed to be post-infectious.

Environmental factors, such as damp, inadequately heated houses and exposure to cigarette smoke also contribute to the

development of bronchiectasis.

N.B. The management of bronchiectasis caused by cystic fibrosis is not discussed in this article.

Socioeconomic factors

Overcrowding and socioeconomic deprivation are important contributing factors to consider in children presenting with

wet cough.1, 2 Discuss strategies to prevent recurrent infection with parents and other caregivers, e.g.

handwashing, cough and sneeze hygiene, seeking medical advice for persistent wet cough and not sharing antibiotics. Refer

to local housing services (e.g. for insulation, curtains, housing assistance) if available and the family is eligible.

Links to local services are available on HealthPathways.

Encourage smoke-free homes

Tobacco smoke is an airway irritant that increases mucus production and impairs airway defences, increasing the risk

of acute RTIs.7 A New Zealand cohort study of children with bronchiectasis found that nearly 60% of household

members reported smoking daily.8 E-cigarettes (or vapes) contain other hazardous compounds and can cause

increased bacterial adherence to airway epithelium.7 Parents or caregivers who smoke should be encouraged

to stop, or at least smoke or vape outside of the house or car; refer them to smoking cessation services for additional

support if required.

For further information on smoking cessation, see: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2015/October/smoking.aspx

Check that children are up-to-date with their immunisations

Some vaccine-preventable illnesses, e.g. pertussis, pneumonia secondary to measles or other infections, can lead to

bronchiectasis. Therefore, it is important to ensure children are up-to-date with their childhood immunisations.

Children at high risk of bronchiectasis should be offered annual influenza vaccination; all children aged under five

years are recommended to receive vaccination, but vaccination is only funded for children who meet eligibility criteria,

which includes chronic respiratory disease with impaired lung function.9

The 10-valent protein pneumococcal vaccination (PCV10 – Synflorix) is funded for all children as part of the childhood

immunisation schedule. Children with chronic pulmonary disease are funded to receive additional vaccination with PCV13

(Prevenar 13), which provides broader coverage against pneumococcal disease. Protection against the strains covered by

PVC10 and PCV13 is lifelong. The polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccination 23PPV (Pneumovax 23) provides even broader coverage

and is also recommended and funded for children with chronic pulmonary disease, but protection only lasts for two to five

years. Additional vaccination with PCV13 and 23PPV is recommended, but not funded, for children who have had an episode

of invasive pneumococcal disease.9

Tuberculosis immunisation is recommended and funded for infants at high risk of tuberculosis infection (see link below).

Most cases in New Zealand are in people born in high incidence countries, e.g. India, China, Indonesia, the Philippines,

Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and South Africa.10, 11 Most children with tuberculosis contract the infection

from someone in their immediate or extended family.11

For the full lists of conditions and criteria that qualify a child for funded vaccinations, see:

Treat wet cough with antibiotics

Chronic wet cough is a cardinal symptom of a persistent RTI, which is a risk factor for bronchiectasis. Starship Guidelines

(2019) recommend managing children aged ≤ 14 years with wet cough lasting more than four weeks as suspected protracted

bacterial bronchitis and treating with a 14-day course of antibiotics (where serious underlying causes have been excluded

– see: “Diagnosing and managing bronchiectasis”).12 While clinicians should always consider the principles

of antimicrobial stewardship when prescribing antibiotics, a lower threshold for treatment may be appropriate for children

who are at high risk of bronchiectasis.

Selecting an antibiotic

Antibiotic choice should be based on sputum culture susceptibility testing, where possible.13 In the absence

of susceptibility data, initiate antibiotic treatment empirically, with the choice targeted to common respiratory bacteria

(Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis) and guided

by local antibiotic sensitivities.14 Appropriate first choices include amoxicillin or trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole

(co-trimoxazole).15 Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid is recommended for empiric use in some guidelines, however,

expert opinion is that this treatment should be reserved for children with a confirmed diagnosis of bronchiectasis.

If sputum culture is positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus aureus, refer

for paediatric assessment as this may indicate undiagnosed cystic fibrosis.

Best practice tip: Obtaining a sputum sample from children can be difficult and is usually not possible in younger children,

e.g. aged under around seven years. Techniques that may help children to produce a sample include getting them to inhale

deeply then attempt a deep cough on exhalation. Tapping gently on the child’s chest may help to loosen sputum in the lungs.

A tongue depressor may be used to stimulate cough, if needed.

Arrange a chest X-ray

Refer all children who have had a wet cough for more than four weeks and have been treated with antibiotics for at least

two weeks (see below) for a chest X-ray. Chest X-ray is indicated whether or not the cough has resolved with treatment

and would ideally be performed when the child is well.15 If the chest X-ray is abnormal, refer for paediatric

assessment.15

N.B. Chest X-ray can be insensitive for detecting bronchiectasis. Therefore, if symptoms recur or persist despite a

normal chest X-ray, manage as below and if there is no response to a second course of antibiotics, refer for paediatric

assessment.

Ongoing management

If cough persists after the initial treatment period, another 14-day course with an alternative antibiotic is recommended.12,

15 Consider seeking written or phone advice from a paediatrician to guide antibiotic choice for the second course.

If cough still persists after the second course, refer for paediatric assessment.2 If the child responds

to antibiotic treatment and there are no chest X-ray abnormalities, the diagnosis of protracted bacterial bronchitis

is confirmed and recurrences can be treated with a 14-day course of antibiotics.12, 15

If there are more than three recurrences per year, this may be indicative of progression of protracted bacterial bronchitis

to bronchiectasis and the child should be referred for paediatric assessment.15

The earlier bronchiectasis is diagnosed in children, the greater the opportunity to limit its progression.16,

17 In some cases, prompt detection may even allow for partial or complete reversal of the condition.16,

17 This has not been shown in adolescents or adults with bronchiectasis. All children with suspected bronchiectasis

(see below) should be referred for paediatric assessment. Diagnosis is confirmed by chest CT in secondary care.

Consider bronchiectasis in children with recurrent wet cough

Bronchiectasis is characterised by recurrent wet or productive cough episodes (more than three per year), each lasting

for more than four weeks. Other symptoms or signs that may be present include:3, 13

- Breathlessness on exertion

- Symptoms of airway hyper-responsiveness

- Growth restriction

- Digital clubbing

- Hyperinflation

- Chest wall deformity

- Crackles on auscultation

- Wheeze – there may be co-existent asthma or can occur with airflow turbulence caused by excessive bronchial secretions

Other serious underlying causes that should be considered when assessing a child with chronic wet cough include undiagnosed

cystic fibrosis and tuberculosis infection.

For further information on diagnosing bronchiectasis in children, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2012/September/bronchiectasis.aspx

Refer children with suspected bronchiectasis for paediatric assessment

Indications for referral to a paediatrician based on suspicion of bronchiectasis include:13

- Persistent wet cough not responding to four weeks of antibiotics (i.e. an initial 14-day course, followed by a second

14-day course due to a lack of response)

- Three episodes of chronic (lasting more than four weeks) wet cough per year responding to antibiotics

- Symptoms or signs on examination suggestive of chronic respiratory disease

- A chest X-ray abnormality

Consider arranging the following investigations while awaiting outpatient assessment:13

- Baseline tests: full blood count and major immunoglobulin classes (IgG, IgA, IgM, IgE)

- Sputum sample for culture (if possible, depending on the child’s age) – if H. influenzae is detected (and

especially if more than once), there should be a high suspicion of bronchiectasis

- Chest X-ray – if not already done

- Spirometry (if possible, depending on the child’s age)

If the child has had a wet cough lasting more than four weeks, initiate antibiotic treatment while awaiting referral.

An acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis in children is defined as increased frequency or severity of wet cough for three

or more days; other symptoms such as lethargy, chest pain, breathlessness, haemoptysis, fever or coughing to the point

of vomiting, may also be present.7, 14

The patient should have an action plan for managing exacerbations, which may include keeping a home supply of antibiotics.

Ensure parents or other caregivers understand the plan and provide them with encouragement and support to engage with

strategies to prevent exacerbations, e.g. warm, dry and smoke-free homes, influenza and additional pneumococcal vaccinations

(funded for children with bronchiectasis), hand, cough and sneeze hygiene practices to prevent infection, regular exercise.

All children with bronchiectasis should be reviewed by a paediatrician – the frequency is determined by disease severity.

Seek advice from a paediatrician for children who have frequent exacerbations, e.g. three or more per year, as long-term

antibiotic treatment may be necessary.13 Azithromycin is funded with Special Authority approval for bronchiectasis

prophylaxis; applications must be made by a paediatrician or respiratory physician.

An example of a bronchiectasis action plan is available from:

www.kidshealth.org.nz/sites/kidshealth/files/pdfs/Bx_action_plan.pdf

Antibiotics are the key treatment for managing exacerbations

Antibiotics are the mainstay pharmacological treatment of patients with bronchiectasis exacerbations, reducing airway

bacterial load and preventing future exacerbations.6 Up to 50% of exacerbations may be triggered by a viral

infection, however, antibiotic treatment is indicated even if a viral aetiology is suspected to reduce airway microbial

load.3, 7 Ideally, a sputum sample should be obtained for susceptibility testing to guide antibiotic choice

to treat an exacerbation. If this is not possible, review the results of any previous sputum culture and base treatment

on that.13 If a sputum sample is not possible, e.g. in younger children, antibiotic treatment should be initiated

empirically. A 14-day course of amoxicillin + clavulanic acid is often used first-line for children with a confirmed diagnosis

of bronchiectasis; other choices include amoxicillin, trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole, cefaclor or erythromycin.3

If susceptibility testing reveals bacterial resistance and symptoms are not improving, the antibiotic should be changed

to a suitable alternative (narrow spectrum, if possible).14 If symptoms are improving, the antibiotic can

be continued, even if resistance is shown. If susceptibility testing is not possible, e.g. due to the child’s age, and

symptoms are not improving, consider changing to another antibiotic or seek advice from a paediatrician. This decision

will likely be based on factors such as how unwell the child is, how many exacerbations they have had previously, their

past response to antibiotic treatment and which antibiotic was used.

If sputum culture indicates the presence of P. aeruginosa, paediatric consultation is recommended as eradication

is more aggressive and may require hospital admission, intravenous or nebulised antibiotics.

Chest physiotherapy

Following referral from a paediatrician or general practitioner, a physiotherapist will create an individualised airway

secretion clearance programme for the child, and provide instructions for parents or caregivers on how to carry out the

treatment at home. Chest physiotherapy should be performed once or twice daily when the child is well, and should

be intensified if cough increases or exacerbation occurs, as indicated by their action plan. Mechanical clearance of airway

secretions reduces secretion accumulation, airway blockage and inflammation, and limits the opportunity for infection.6 Commonly

used techniques in children include percussion, autogenic drainage and use of a positive-expiratory-pressure (PEP) device.6 Ensuring

that the family understands how and when to carry out the exercises is key to how adherent they are likely to be to the

programme. Refer parents or other caregivers back to the physiotherapist if additional support or education is needed.

Regular exercise such as playing or kicking a ball with siblings or friends, running around the playground, riding bikes,

going for a walk around the neighbourhood or playing sports, should also be strongly encouraged for airway clearance,

in addition to its other physical and psychosocial benefits.

Corticosteroids and bronchodilators should not be prescribed routinely

Inhaled and oral corticosteroids are not recommended to treat bronchiectasis unless the child also has an established

diagnosis of asthma.13 There is no evidence of benefit in the absence of airway eosinophilia.7 Inhaled

bronchodilators are not recommended routinely, but may be considered if the child has wheeze.13

Follow-up to assess treatment effectiveness

All children who have been treated for an acute bronchiectasis exacerbation should be followed up within 48–72 hours

by phone or in person, depending on how unwell they were at their initial presentation, to assess treatment effectiveness.

If the child has not improved, seek advice from a paediatrician; hospital admission for intravenous antibiotics may be

required in some cases.