Key Practice Points

- Identify patients with HCV infection by testing those at high risk

- Testing begins with serology for anti-HCV antibodies

- Positive serology must be followed by an HCV RNA assay or HCV core antigen assay

- HCV RNA quantitation and HCV genotype testing are no longer required

Hepatitis C infection occurs through exposure to infected blood or body fluids.1 The majority of newly

acquired infections in New Zealand are from injectable drug use.2 Promoting the use of clean needles for

people using injectable drugs is important to reduce new infections. If people using injectable drugs are not already

receiving assistance, they should be referred to community alcohol and drug services (CADS) and a local needle exchange

service.

For a list of facilities involved in the New Zealand needle exchange programme, see:

www.nznep.org.nz/outlets

Some patients with hepatitis C will have acquired iatrogenic infection from contaminated blood products, used in New

Zealand prior to July 1992. Others may have become infected following medical or dental procedures, particularly if these

were performed in countries with high HCV prevalence and/or poor infection control procedures.1, 3 Regions

with high HCV prevalence include Eastern Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, Western and Central Sub-Saharan Africa,

Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent.1, 3 People who have been incarcerated are also at high risk, due

to the prevalence of HCV in the prison population and the use of potentially contaminated tattooing equipment. Sexual

transmission plays a minor role in the spread of hepatitis C and the risk is greatest for men who have sex with men, heterosexuals

with multiple partners and sex workers, especially in association with injectable drug use.4

People cannot develop immunity to HCV. Therefore, anyone who has eradicated HCV infection either spontaneously or following

antiviral treatment may be re-infected.

Initial infection is usually asymptomatic

The majority of people who contract HCV are asymptomatic in the acute stages of infection with only 25–30% of people

noticing symptoms.5 The symptoms of acute HCV infection are nonspecific and include:6

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Abdominal pain

- Muscle aches

- Jaundice

Substantially elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, e.g. greater than ten times the upper limit of normal,

occur two to eight weeks after infection.7 These levels typically spontaneously decrease to within normal

limits within three to six months.8 Acute HCV infection is a Notifiable disease.

Viral clearance without treatment is possible

It is estimated that 20–25% of people infected with HCV clear the virus without medical intervention.1 Females,

younger patients, and patients who develop symptoms, such as jaundice, are more likely to achieve spontaneous viral clearance.1 Patients

of Polynesian and Asian ethnicity are also more likely to achieve clearance due to genetic differences associated with

higher rates of spontaneous viral clearance.9, 10

The majority of patients develop long-term infection

Approximately three out of four people infected develop long-term HCV infection, placing them at increased risk of hepatic

complications and making transmission of the virus more likely. Due to the slow disease process many people will be unaware

of the infection. Liver function tests may be persistently normal in more than one-quarter of people with chronic HCV

infection.11 People who present with symptoms of liver disease may have acquired HCV at a younger age, and

the source of infection may never be identified.

In people with long-term HCV infection the risk of cirrhosis increases with the duration of infection; 20–30% of patients

develop cirrhosis after 20–30 years with 2–4% of these people per year developing hepatocellular carcinoma.1, 3

Identify patients who are most likely to have been infected with HCV through their personal and maternal history. The

majority of people with chronic HCV infection in New Zealand have used injectable drugs.12

Risk factors for HCV infection include:1, 3, 13

- Injectable drug use

- Receiving a blood transfusion in New Zealand prior to July, 1992

- Migration from or receiving health care in a region with high HCV prevalence

- Time spent in prison

- A tattoo, body piercing or alteration, e.g. scarification, which was not performed in a licenced premises within New

Zealand, i.e. either performed in prison or in a country with a high prevalence of HCV

- History of acute hepatitis, jaundice, or abnormal liver function

- Being born to an HCV infected mother; mother to infant transmission occurs in approximately 5% of infected mothers14

It is recommended that all patients with these risk factors undergo testing for HCV infection.1 In

practice, a reasonable approach is to offer HCV testing to patients with risk factors and ensure that new patients with

risk factors are identified on enrolment.

For further information on strategies for identifying patients at risk and discussing HCV testing, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/2017/hepc.aspx

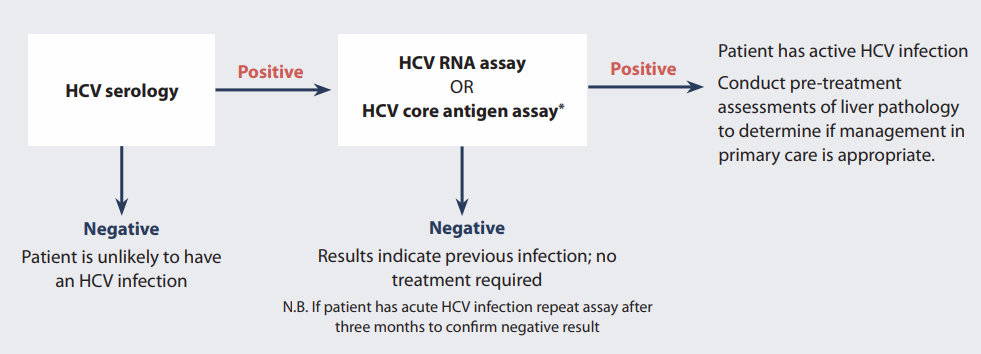

The HCV testing process

Diagnosing HCV infection typically involves two tests; some laboratories may perform these as reflex tests:

- Screening test for HCV exposure: anti-HCV antibodies

- Confirmatory test for active HCV infection. Either*:

- a. HCV RNA assay

- OR

- b. HCV core antigen assay †

* Some laboratories may perform these as reflex tests

† Anticipated to be available at some stage during 2019

Additional tests for other forms of hepatitis and HIV are generally requested at the same time.

For further information on the diagnosis and management of hepatitis B, see: www.bpac.org.nz/2018/hepb.aspx

Testing starts with HCV serology

Serology is the first-line test for investigating HCV infection in the majority of patients (Figure

1). Antibodies to

HCV may take up to six months to develop and only 50% of patients are likely to have positive serology during the acute

stage of infection; delayed testing may be appropriate for these patients.15 Discuss the limitations of testing

with patients with ongoing risk of infection, e.g. current injectable drug users, and the delay between infection and

HCV antibody production.

Negative serology indicates the absence of HCV infection, unless the patient is immunosuppressed or they

have an acute HCV infection.

Positive serology indicates either a current or previous HCV infection, or a false positive, and must be

followed by an HCV RNA or HCV core antigen assay to determine if the patient has a current infection (see below).

* Anticipated to be available at some stage during 2019

Figure 1: Testing patients for HCV infection.22, 23

HCV serology is not diagnostic for hepatitis C

Serology tests have a high sensitivity and specificity, although false positive results do occur. The proportion of

false positive results depends on the background prevalence of hepatitis C; in populations with a low prevalence, false

positive results can account for up to 35% of positive results.16 Testing patients without risk factors for

HCV infection is therefore not recommended. Serology must be followed by HCV RNA testing to determine if the infection

is current.16 If a patient has a positive serology and a negative HCV RNA or HCV core antigen test

they are not currently infected and do not require treatment.

False negatives are uncommon: it is estimated that 99% of patients with a long-term infection and detectable HCV RNA

or HCV core antigen will test positive for anti-HCV antibodies.17

A positive HCV RNA assay or HCV core antigen assay confirms current infection

HCV RNA detected through a polymerase chain reaction assay detects and quantifies viral RNA (Figure 1). In acute infection,

HCV RNA can be detected within one to two weeks of exposure and levels increase two to eight weeks after infection.7

It is anticipated that an alternative test for current infection, the HCV core antigen assay, will become available

at some stage during 2019. These will be performed as reflex tests in patients who test positive for anti-HCV antibodies.

The HCV core antigen assay detects viral antigens produced during HCV replication.18 It is less sensitive

than an HCV RNA assay and may not detect very early HCV infection.19 However, a positive HCV core antigen

test can reliably confirm established chronic infection, with a sensitivity of 93.4% and specificity of 98.8% compared

to an HCV RNA assay.20 As is the case with the HCV RNA assay, a negative HCV core antigen assay at 12 weeks

after completion of antiviral therapy confirms successful HCV eradication.20, 21

A positive HCV RNA or HCV core antigen result indicates current infection, either acute or long-term (see:

“Conservative management is generally appropriate for acute infection”). Patients should be informed of positive results

in person and counselled about transmission prevention (see “Advice for patients to reduce the risk

of HCV transmission”).

A negative HCV RNA or HCV core antigen assay indicates the patient does not have current infection and

does not require treatment. For patients diagnosed during the acute stage of infection, repeat testing after three months

is recommended to confirm the negative result.15

HCV genotyping is no longer required

Previously, HCV genotyping was required to determine eligibility for treatment, as Viekira Pak regimens are only effective

against HCV genotypes 1 and 4. From 1 February, 2019, genotype testing is no longer required as glecaprevir + pibrentasvir

(Maviret) is effective against all HCV genotypes.6

Conservative management is generally appropriate for acute infection

A watch and wait approach is reasonable for patients during the acute phase of infection, with ongoing HCV RNA or HCV

core antigen testing for viral clearance and monitoring of liver function.1 It is estimated that 20–25% of

people infected with HCV clear the virus without medical intervention.1 The majority of patients who clear

the virus spontaneously do so within 12 weeks of infection.7

In the first few months of infection, viral RNA and core antigen levels can fluctuate. Testing should continue for six

months or until spontaneous clearance is confirmed or deemed unlikely. Patients are regarded as having cleared an HCV

infection if there are at least two HCV RNA or HCV core antigen tests below the level of detection, performed at least

one month apart.1

Acute HCV infection can be treated with interferon-based regimens, with a shorter duration, simpler treatment regimen

and greater success rate than that used for long-term HCV infection; discussion with a gastroenterologist may be appropriate,

e.g. if patients have more severe symptoms, hepatic impairment or co-infection with HIV.1, 6

References

- Hepatitis C Virus Infection Consensus Statement Working Group. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatitis

C virus infection: a consensus statement. Melbourne: Gastroenterological Society of Australia 2018. Available from:

www.asid.net.au/documents/item/1208 (Accessed

Jan, 2019).

- Institute of Environmental Science and Research Limited (ESR). Notifiable diseases in New Zealand annual report. 2016.

Available from:

https://www.esr.cri.nz/digital-library/notifiable-diseases-annual-surveillance-summary-2016/ (Accessed Jan, 2019).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Guidelines for the screening, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis

C infection. Geneva: WHO 2016. Available from:

www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hepatitis-c-guidelines-2016/en/ (Accessed Jan, 2019).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Draft global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, 2016-2021 - the first of

its kind. Geneva: WHO 2016. Available from:

http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_32-en.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed Jan, 2019).

- Lebovics E, Czobor K. Screening, diagnosis, treatment, and management of hepatitis C: a novel, comprehensive, online

resource center for primary care providers and specialists. Am J Med 2014;127:e11-14.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.10.004

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). HCV guidance:

recommendations for testing, managing and treating and hepatitis C. 2018. Available from:

www.hcvguidelines.org (Accessed Jan, 2019).

- Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) Hepatitis C Working Party. Asian Pacific Association

for the Study of the Liver consensus statements on the diagnosis, management and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection.

J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:615–33.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04883.x

- Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Applegate T, et al. Dynamics of HCV RNA levels during acute hepatitis C virus infection.

J Med Virol 2014;86:1722–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24010

- Jiménez-Sousa MA, Fernández-Rodríguez A, Guzmán-Fulgencio M, et al. Meta-analysis: implications of interleukin-28B

polymorphisms in spontaneous and treatment-related clearance for patients with hepatitis C. BMC Medicine 2013;11:6.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-6

- Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance.

Nature 2009;461:399–401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature08309

- Puoti C, Guarisco R, Spilabotti L, et al. Should we treat HCV carriers with normal ALT levels? The ‘5Ws’ dilemma.

J Viral Hepat 2012;19:229–35.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01485.x

- Gane E, Stedman C, Brunton C, et al. Impact of improved treatment on disease burden of chronic hepatitis C in New

Zealand. N Z Med J 2014;127:61–74.

- Ministry of Health (MoH). Hepatitis C. 2018. Available from:

www.health.govt.nz/your-health/conditions-and-treatments/diseases-and-illnesses/hepatitis-c (Accessed Jan, 2019).

- Benova L, Mohamoud YA, Calvert C, et al. Vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: systematic review and meta-analysis.

Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:765–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu447

- European Association for Study of Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection.

J Hepatol 2014;60:392–420. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.003

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for laboratory testing and result reporting of antibody to

hepatitis C virus. MMWR Recomm Rep 2003;52:1–13.

- Pawlotsky J-M. Use and interpretation of virological tests for hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002;36:S65-73.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2002.36815

- Freiman JM, Tran TM, Schumacher SG, et al. Hepatitis C core antigen testing for diagnosis of hepatitis C virus infection:

a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:345–55.

http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/M16-0065

- Lamoury FMJ, Soker A, Martinez D, et al. Hepatitis C virus core antigen: A simplified treatment monitoring tool, including

for post-treatment relapse. J Clin Virol 2017;92:32–8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2017.05.007

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing. WHO 2017. Available from:

www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/guidelines-hepatitis-c-b-testing/en/ (Accessed Jan, 2019).

- Rockstroh JK, Feld JJ, Chevaliez S, et al. HCV core antigen as an alternate test to HCV RNA for assessment of virologic

responses to all-oral, interferon-free treatment in HCV genotype 1 infected patients. J Virol Methods 2017;245:14–8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2017.03.002

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Testing for HCV infection: an update of guidance for clinicians

and laboratorians. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:362–5.

- New Zealand Society of Gastroenterology. NZ Society of Gastroenterology HCV treatment guidelines. 2016. Available

from:

https://nzsg.org.nz/assets/Uploads/NZSG-Hepatitis-C-Guidance-November-UPDATE.pdf (Accessed Jan, 2019).