The New Zealand adult asthma guidelines were released by the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation of New Zealand in November, 2016.

The Guidelines recommend a stepwise approach to the pharmacological management of asthma in adults, with an emphasis on managing future risk of exacerbations.

A four-stage consultation is recommended as a framework for managing adults with asthma in primary care: assess control of symptoms,

consider other clinically relevant issues, adjust pharmacological treatment and complete an asthma action plan.

Asthma medicines should be “stepped up” if patients have uncontrolled symptoms or a recent exacerbation, and potentially “stepped down” if symptoms are under control.

A key decision is when to initiate an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS); the Guidelines recommend a low threshold for stepping up treatment if patients are experiencing symptoms,

depending on their treatment goals. If symptoms are still uncontrolled despite adherence to an ICS, it is recommended to add a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA)

to the patient’s regimen, rather than increasing the ICS dose.

Recommended escalation of asthma treatment for adults:

Step 1 SABA (short-acting beta2-agonist) reliever

Step 2 ICS preventer inhaler with SABA reliever

Step 3 Combination ICS/LABA inhaler; either as a single inhaler preventer + reliever or with a SABA reliever

N.B. Management strategies at Step 4 and 5 involve increasing the ICS dose and adding additional treatments such as

sodium cromoglicate, sodium nedocromil, montelukast, theophylline or tiotropium.

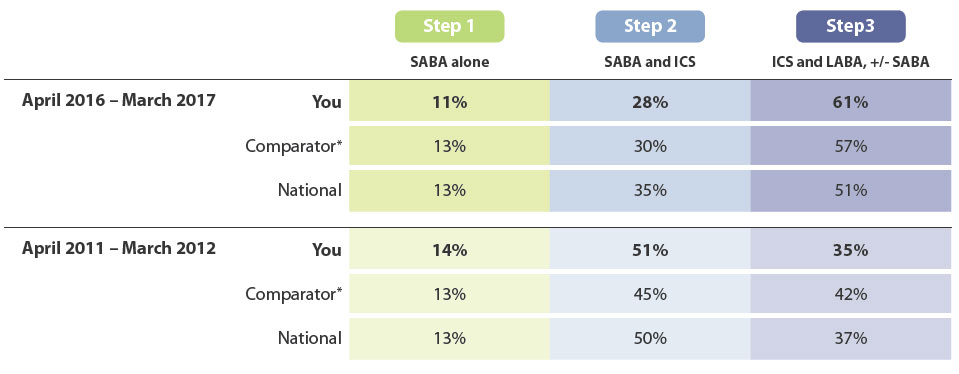

Your Patients

In 2016/2017 Sample Medical Centre had 500 patients aged ≥18 years who received an inhaled asthma medicine. The figures

and tables below show the proportion of these patients on each treatment step, along with data for similar practices and nationally.

For comparison, we have shown the same data for 2011/2012; at a national level, the proportion of patients on Step 3 (ICS + LABA) has

increased considerably. This is likely to be largely due to widened access and subsidy of ICS/LABA combination inhalers, but may also

reflect a more proactive approach to escalating treatment.

How does your prescribing compare to that of your peers? Consider the factors which contribute to your decision to escalate treatment in adults with asthma.

* See below for explanation

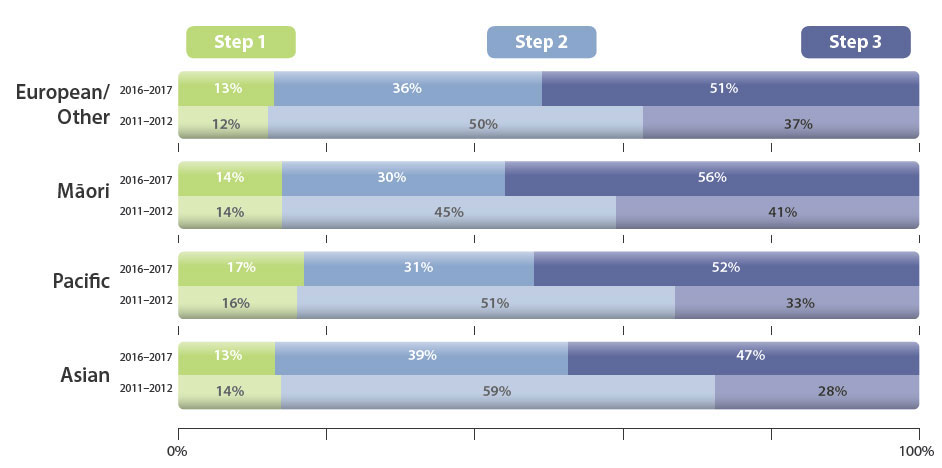

National Data by Ethnicity

Māori and Pacific peoples are more severely affected by asthma, and are more likely to be hospitalised or die due to asthma than people of other ethnicities in New Zealand.1

Given the increased severity of asthma that affects this group of patients, it would be expected that their treatment would be escalated earlier and at a higher rate

compared to others. Overall, the proportion of patients receiving treatment at Step 3 has increased for all ethnicities since 2011/12. The Figure shows that a

higher proportion of Māori patients are receiving treatment at Step 3 (ICS + LABA, +/– SABA) compared to patients of other ethnicities, which is encouraging.

However, given that Pacific patients also have worse outcomes in asthma, it would be expected that they too would have a greater proportion receiving

treatment at Step 3. Practices can consider their own patient population and ensure that the right steps are taken to intensify treatment as appropriate.

Identify adults with asthma in your practice most at risk and consider what you can do to improve outcomes:

expand on one aspect of asthma education at every consultation, assess symptom control and adherence to treatment, manage other clinical factors, optimise medicines.

For further information, see: “Managing adults with asthma in primary care: the four stage consultation”

1. Barnard L, Baker M, Pierse N, et al. The impact of respiratory disease in New Zealand: 2014 update.

2015. Available from:

www.asthmafoundation.org.nz/research/the-impact-of-respiratory-disease-in-new-zealand-2014-update (Accessed Apr, 2017).

Determining the data set

This data includes patients aged ≥ 18 years dispensed a SABA, ICS or LABA. Any patients dispensed an inhaled anticholinergic medicine

(e.g. tiotropium, ipratropium) or only one SABA in the 12 month period have been excluded from this report. The resulting data set is a

representation of adults with asthma, but may also include some patients with COPD who were dispensed a SABA or LABA and ICS but not an anticholinergic medicine.

An alternative way to exclude patients with COPD from the data set would be to limit the age range to 18 – 35 years, as COPD is an unlikely diagnosis

in this age group. Using this age range, we found that the national figures were largely unchanged, but individual prescriber’s data was less meaningful

due to low patient numbers. Therefore we did not use this method for the report.

Using comparator practices to make your reports more meaningful

The problem with national comparisons

We understand that no two practice populations are the same and therefore it can be difficult to compare your practice’s prescribing to national prescribing levels.

The development of comparator practices

To help combat this problem and make these reports more relevant to you, we have developed comparator groups. In these new reports your practice’s

prescribing will be compared to ten practices from across New Zealand whose patient populations are similar to yours in:

- Gender

- Age

- Ethnicity

- Deprivation

We will account for the size of your registered practice population by using proportions or standardised formats e.g. prescribing per 1000 practice population.

Eliminating some demographic differences mean you will be able to more easily determine meaningful differences in your prescribing practices compared with your comparator practices.

If your prescribing from your practice is different compared to other practices in your comparator group, this may be explained by:

- Your prescribing practice and decision making being different to your peers

- The region you live in, e.g. medicines to treat sore throats and rheumatic fever in the far

north of New Zealand will be higher than in the south

- Someone in your practice may specialise in a particular area of medicine that uses certain medicines

more than others, e.g. dermatology and isotretinoin prescribing

Further investigation of your prescribing

Undertaking an audit or peer group discussion may provide more detail to help identify

similarities and differences in prescribing practice compared

to other primary care practitioners. If any issues have been identified these resources can help instigate change, leading to more appropriate use of

medicines and facilitate best practice.

Feedback

We are always trying to improve our reports therefore we would like to know how useful you find them.

We would also like to hear if you have any further suggestions for presenting and comparing annual prescribing data.

Email us at: [email protected]