Published: July, 2023 | Review date: July, 2026

This audit helps primary care health professionals optimise

the management of patients prescribed opioid medicines

in their practice. The aim is to ensure that patients who have

been using these medicines long-term for the treatment

of non-cancer pain have their medicine regimen regularly

reviewed, in order to determine if ongoing use is appropriate;

withdrawal can be discussed with patients for whom ongoing

use is not indicated. Patients using these medicines for the

management of pain associated with cancer or other palliative

care conditions are not covered by this audit. Clinicians could

also use the audit to assess other medicines used long-term

for the management of chronic pain, such as gabapentin.

Strong opioid medicines are recommended at Step Three of

the World Health Organisation pain ladder, and are typically

reserved for the treatment of severe acute pain or moderate

to severe chronic pain, depending on a patient’s response

to other analgesics. There are few situations when a strong

opioid would be initiated for acute pain in primary care. More

common scenarios for general practitioners are renewing

a prescription of a strong opioid medicine for patients

discharged from hospital, renewing prescriptions of strong

opioids for patients with chronic pain managed in primary

care or initiating or renewing prescriptions of weaker opioids

such as tramadol or codeine.

Opioid medicines are potentially addictive. Dispensing data

from New Zealand show that between 2017 and 2021, almost

one-fifth of the population received an opioid medicine each

year. Discussions regarding addiction to opioid medicines

are often focused on strong opioids such as oxycodone,

however, the same prescribing cautions should be applied

to weaker opioids, such as tramadol, to minimise the risk of

inappropriate use. Dispensing data from New Zealand show

that while weaker opioid use declined slightly between 2017

and 2020, there was an increase in dispensings in 2021.1

For further information on New Zealand trends in opioid

use, see: bpac.org.nz/2022/opioids.aspx

Patients using opioid medicines should be encouraged to

adopt and continue with non-pharmacological approaches

to managing pain, such as exercise, physiotherapy and

relaxation/behavioural techniques. Clinicians can consider

the use of multimodal analgesia, such as using paracetamol

in combination with an opioid medicine, in order to reduce

the dose of opioid medicines required and therefore reduce

a patient’s risk of adverse effects, as well as provide analgesia

when the opioid medicine is withdrawn.

Clinical guidelines recommend that patients should be

reviewed within one to four weeks of initiating an opioid

medicine or increasing dose, as patients can become

dependent as early as one month after initiating opioid

medicines.2, 3 For patients using these medicines longterm, review on a three-monthly basis is recommended (or

more often if required).3

Reviewing patients using opioids

long-term can ensure that the medicines and doses they

are prescribed are still appropriate for their underlying

condition and degree of pain they experience, as well as

allowing the opportunity to assess for the development of

potential adverse effects.

Withdrawing patients who have become dependent on

opioid medicines can be a difficult process, particularly if this

is being managed in primary care without the patient having

access to additional support from addiction services or a pain

clinic in secondary care. The focus of this audit is on identifying

patients who are using opioids long-term and ensuring they

are reviewed. Withdrawing patients from opioid medicines is

not included in the audit process.

For further information on withdrawing patients who are

dependent on opioid medicines, see: bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2014/

October/opioid-addiction.aspx

Summary

This audit identifies patients who have been prescribed

an opioid medicine for three months or more in order to

assess whether the choice of medicine(s) and doses remain

appropriate.4

Recommended audit standards

Ideally, all patients who have been taking an opioid medicine

for the management of non-cancer pain for three months or

more should have a documented discussion in their notes

about the intended duration of opioid medicine use and a

plan for withdrawal. This could also include whether the

addition of another analgesic medicine is appropriate in order

to reduce the dose of opioid medicine(s) required or whether

switching to another analgesic medicine is appropriate. If

there is no documented evidence of a discussion, the patient

should be flagged for review.

Eligible patients

All patients who have been prescribed an opioid medicine for

three months or more are eligible for this audit.

Identifying patients

You will need to have a system in place that allows you to

identify eligible patients. Many practices will be able to

identify patients by running a “query” through their PMS. The

notes of identified patients will need to be reviewed in order

to ascertain the clinical indication for opioid prescription;

patients using opioid medicines to manage pain associated

with cancer or another palliative care condition can be

excluded from the audit.

Sample size

A sample size of 30 patients is sufficient for the purpose of the

audit. However, it is recommended that all eligible patients

using opioid medicines long-term for the management of

non-cancer pain are subsequently reviewed.

Criteria for a positive outcome

A positive result is achieved if a patient who has been

prescribed an opioid medicine for three months or more

has a documented discussion in their notes regarding their

pain management plan. This discussion could include the

expected duration of use of opioid medicines, the use of other

analgesics which could be used in combination with opioids

to help patients manage their pain, non-pharmacological

strategies for pain management and whether withdrawing

from an opioid medicine is appropriate or has been attempted.

During the review, clinicians can consider factors such as:

- Has the patient’s underlying condition changed, e.g. is a greater or lesser extent of pain relief required?

- Is the prescribed opioid medicine still the most appropriate choice?

- Should doses be adjusted or other non-opioid analgesics initiated?

- Should the patient be referred for additional support for non-pharmacological pain management, e.g. to a physiotherapist?

- Does the patient require assistance from addiction services?

Data analysis

Use the sheet provided to record your data. The percentage achievement can be calculated by dividing the total number of patients currently prescribed an opioid medicine for the management of non-cancer pain relief for three months by the number of patients who have a documented pain management plan discussion in their notes.

References

- Pharmaceutical Claims Collection, Ministry of Health, 2022.

- Manchikanti L, Kaye AM, Knezevic NN, et al. Responsible, safe, and effective prescription of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician 2017;20:S3–92

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Guideline for

Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2022. Available

from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/rr/rr7103a1.htm (Accessed May, 2023).

- If this audit is used to identify patients taking other analgesic

medicines long-term, such as gabapentin, clinicians can choose a

timeframe appropriate for the medicine in question

Clinical audits can be an important tool to identify where gaps exist between expected and actual performance. Once completed, they can provide ideas on how to change practice and improve patient outcomes. General practitioners are encouraged to discuss the suitability and relevance of their proposed audit with their practice or peer group prior to commencement to ensure the relevance of the audit. Outcomes of the audit should also be discussed with the practice or peer group; this may be recorded as a learning activity reflection if suitable.

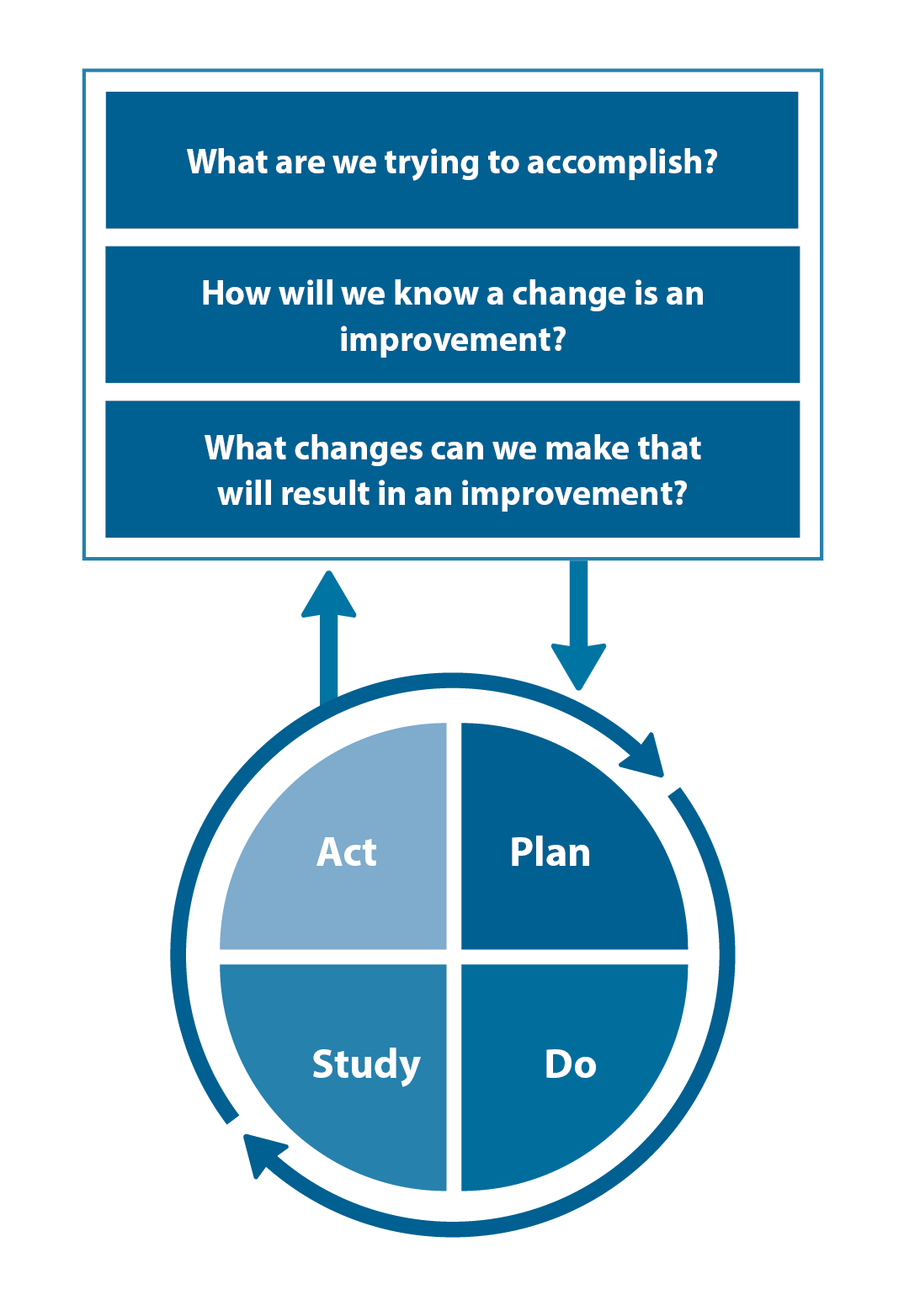

The Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model is recommended by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP) as a framework for assessing whether a clinical audit is relevant to your practice. This model has been widely used in healthcare settings since 2000. It consists of two parts, the framework and the PDSA cycle itself, as shown in Figure 1.

1. The framework

This consists of three questions that help define the “what” and “how” of an improvement project (in this case an audit).

The questions are:

- "What are we trying to accomplish?" – the aim

- "How will we know that a change is an improvement?" – what measures of success will be used?

- "What changes can we make that will result in improvement?" – the concept to be tested

2. The PDSA cycle

This is often referred to as the “engine” for creating, testing and carrying out the proposed changes. More than one cycle is usually required; each one is intended to be short, rapid and frequent, with the results used to inform and refine the next. This allows an ongoing process of continuous learning and improvement.

Each PDSA cycle includes four stages:

- Plan – decide what the change to be tested is and how this will be done

- Do – carry out the plan and collect the data

- Study – analyse the data, assess the impact of the change and reflect on what was learned

- Act – plan the next cycle or implement the changes from your plan

Figure 1. The PDSA model for improvement.

Source: Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement

Claiming credits for Te Whanake CPD programme requirements

Practice or clinical audits are useful tools for improving clinical practice and credits can be claimed towards the Patient Outcomes (Improving Patient Care and Health Outcomes) learning category of the Te Whanake CPD programme, on a two credit per learning hour basis. A minimum of 12 credits is required in the Patient Outcomes category over a triennium (three years).

Any data driven activity that assesses the outcomes and quality of general practice work can be used to gain credits in the Patient Outcomes learning category. Under the refreshed Te Whanake CPD programme, audits are not compulsory and the RNZCGP also no longer requires that clinical audits are approved prior to use. The college recommends the PDSA format for developing and checking the relevance of a clinical audit.

To claim points go to the RNZCGP website: www.rnzcgp.org.nz

If a clinical audit is completed as part of Te Whanake requirements, the RNZCGP continues to encourage that evidence of participation in the audit be attached to your recorded activity. Evidence can include:

- A summary of the data collected

- An Audit of Medical Practice (CQI) Activity summary sheet (Appendix 1 in this audit or available on the

RNZCGP website).

N.B. Audits can also be completed by other health professionals working in primary care (particularly prescribers), if relevant. Check with your accrediting authority as to documentation requirements.