Key practice points:

- Lead is a common environmental pollutant associated with a variety of long-term health complications; lead exposure

in children is particularly concerning as it can have irreversible neurobehavioural and developmental effects that continue

into adulthood

- In many cases, people do not present with symptoms of lead poisoning in primary care; instead they may seek evaluation

due to concerns over a recent exposure event, or engage in work/hobbies with an increased risk of exposure which prompts

further investigation

- Lead exposure is challenging to detect based on symptoms alone as the most common presentation involves non-specific

gastrointestinal and neurological features; if a patient does present with these features, consider lead toxicity in your

differential diagnosis, enquire about possible exposure events, and investigate further by testing blood lead levels if

needed

- On 9 April, 2021, the level at which lead absorption becomes a notifiable condition to a Medical Officer of Health was

reduced to ≥0.24 micromol/L

- Electronic reporting of notifiable lead exposure to Public Health Units can be made through the Hazardous Substances

Disease and Injury Reporting Tool (HSDIRT); this is available via Medtech, Indici, MyPractice and Profile patient management

systems

- All patients with elevated blood lead levels should receive education about reducing the risk of future exposure, and

the Public Health Unit will advise on management and follow-up as required, e.g. remediation of environmental sources of

lead, repeat blood lead testing requirements, and the need for secondary care referral (where chelation treatment is available

for severe acute poisoning)

Lead is a common and persistent pollutant found in a variety of environmental and occupational sources (Table

1).1, 2 Following the removal of lead from petrol in 1996, the most common source of exposure in New Zealand

is from lead-based paint used in pre-1980s houses (particularly those built before 1945).3 The primary routes

through which lead enters the body are ingestion or inhalation.2 It is estimated that 50% of the lead deposited

in the respiratory tract is subsequently absorbed into the systemic circulation, whereas 5–15% of ingested lead is absorbed

through the gastrointestinal mucosa.2

Once lead enters the blood, it acts as a cumulative toxicant, building up progressively in various body systems following

each exposure event, e.g. brain, kidney, liver and bones.4 In pregnant females, lead can cross the placenta to

the developing fetus, which may result in miscarriage, stillbirth, premature birth or low birth weight.2 Approximately

70–95% of absorbed lead is deposited in bones; given that the half-life of lead is decades, this can serve as a reservoir

for re-release into systemic circulation and soft tissues over time.2 The mobilisation of lead from bones may

increase in response to specific biological processes, e.g. pregnancy and menopause.4 As such, people may present

with various symptoms depending on the magnitude or duration of exposure, and their individual characteristics, e.g. age,

co-morbidities (see: “Assessing potential cases of lead exposure in primary care”).5

Table 1. Environmental sources of lead and risk factors for exposure.1, 4

| Environmental sources |

Risk factors for exposure |

Lead-based household paints (most common)

- Almost certainly present in pre-1945 paintwork

- Likely to be present in pre-1980 paintwork

- Particularly common in Housing New Zealand properties

|

- Painting

- Mining

- Smelting/metal working

- Soldering

- Automotive repair

- Metal recycling

- Renovating older houses

- Glazed pottery making

- Battery manufacturing

- Fishing sinker manufacturing

- Target/indoor rifle shooting and bullet casting

- Stained glass window making

- Pica

|

| Old toys, cots or jewellery, particularly those manufactured overseas, which may contain

lead-based paints |

| Household dust (which can potentially contain dust from deteriorating lead-based paintwork) |

Water, particularly from:

- Rainwater tanks contaminated by lead-containing dust, e.g. from the roof or guttering

- Older homes that contain lead pipes or valves/fittings soldered with lead which leaches directly into the water

(N.B. all known lead piping in New Zealand reticulated water systems has been replaced)

Soil contaminated by:

- Previous industrial activities or mining

- Deteriorating or removed lead-based paint

|

| Certain types of machinery containing lead-based components, e.g. car radiators |

| Some imported cosmetics, e.g. lipsticks, or traditional medicines, e.g. ayurvedic remedies

and traditional Chinese medicinal herbs |

| Ammunition containing lead |

| Food stored in environments or workplaces containing lead contamination |

Due to the public health implications associated with environmental exposure, lead absorption is a notifiable condition

if blood levels are greater than a certain threshold (see: “Reporting of notifiable lead absorption”).

In 2019, the notification rate for lead absorption in New Zealand was 5.0 per 100,000 population (204 total), double the

rate in 2017.* 6 This increase was predominantly due to higher numbers of adult notifications, with rates of

elevated blood levels in children aged 0–14 years remaining relatively consistent since the early 2000s.6

Since 2014, notifiable rates of lead absorption have been consistently higher in:6

- People aged 45–64 years

- Pacific peoples

- People living in low socioeconomic areas

- Males

Occupational exposure. Painters are consistently the occupational group with the most lead absorption

notifications in New Zealand, accounting for approximately 40% of work-related cases in 2019.6 Other high ranking

groups include metal workers and those working in radiator repair.6

Non-occupational exposure. The most common sources of non-occupational lead exposure are lead-based paints,

indoor rifle ranges, bullet/sinker manufacturing, or unknown causes.6 Levels of lead absorption are generally

lower in people with non-occupational exposure; in 2019 the levels in reported cases ranged from 0.48–0.71 micromol/L.6

*N.B. The statistics presented in this section are based on a blood lead notification threshold

of ≥0.48 micromol/L, which has since been lowered (for more information, see: “On 9 April, 2021, the lead

absorption notification level reduced”). As a result, there likely would have been many cases of lead absorption which

were not reported that would qualify as notifiable cases now.

The burden of disease associated with lead exposure

Lead exposure can have both acute and chronic consequences. Although absorbed lead can affect a wide

range of organs, the nervous system is considered the most vulnerable to lead-related toxicity.4 Initial

symptoms may range from those that are relatively mild (e.g. headache and absentmindedness) through to severe complications

such as encephalopathy (see: “Assessing potential cases of lead exposure in primary care”).4

Cardiovascular effects are also a prominent concern in the long-term, with lead exposure increasing the risk of hypertensive

heart disease, ischaemic heart disease and stroke.1 Elevated lead levels in the blood are associated with

an increased risk of all-cause mortality, as well as death due to cardiovascular disease.2 There is also

evidence that lead exposure increases the risk of lung, stomach, kidney, bladder and brain cancer, and it is a potential

cause of anaemia, kidney damage and impaired sperm production.2, 5

Childhood lead exposure is particularly concerning. Children aged under six years are at a higher

risk of lead exposure due to their increased tendency to engage in hand-to-mouth behaviours.6 In addition,

their diets may be lower in calcium and iron; deficiencies in these essential nutrients can increase the absorption

and toxicity of lead.7 It is estimated that children absorb four to five times more ingested lead from any

given source compared with adults.1 The developing nervous system in children means they are more susceptible

to the irreversible neurobehavioral and developmental effects of lead, even at low levels

(see: “Why were the notification levels lowered further?”).4

Investigating people with potential lead exposure. In general, symptoms of lead poisoning do not appear

immediately after exposure.5 However, people without any presenting features will sometimes seek primary care

evaluation due to concern over a recent lead exposure event, e.g. a community exposure. In such cases, it is important to

identify the potential source, the quantity of lead potentially consumed, and the chronicity of exposure.5 If

there is significant clinical concern over the exposure event, then it is reasonable to request a blood lead level test,

particularly in children, females of childbearing age, pregnant females, or in people with a household member who has recently

tested positive for raised lead levels.

Investigating symptomatic people. In very rare cases, people may present with symptoms of lead poisoning

following several days, weeks or even months of sustained exposure, yet be unaware that lead is the potential cause.5 Early

symptoms are generally non-specific, predominantly affecting the gastrointestinal tract and nervous system:4

- Possible gastrointestinal symptoms: reduced appetite, nausea, diarrhoea or constipation, weight loss

and stomach pain

- Possible neurological symptoms: headaches, mood disturbances (e.g. irritability or depression), memory

impairment and tingling/numbness in the fingers and hands; in severe cases, lead-induced toxicity may present as encephalopathy,

i.e. the patient may exhibit an altered mental state – if this is suspected, request an emergency assessment in secondary

care.

- Constitutional symptoms: excessive fatigue, decreased libido, sleep disturbances

Identifying lead as the possible cause of symptoms in this scenario can be very challenging. Lead poisoning may be suspected

early as the cause based on the patient’s history – including employment and hobbies – or become apparent later as a possible

cause after differential diagnoses have been excluded. For parents of young children with suspected lead poisoning, it can

be useful to ask questions such as:

- Does your child frequently put non-edible objects in their mouth?

- Do they suck their thumb or bite their nails?

- Do they have an old painted cot or any old painted toys?

Monitoring people at high risk. For people with higher-risk occupations, e.g. painting contractors (including

self-employed), blood lead level surveillance may be considered a routine requirement under the Health and Safety at Work

Act 2015.3 The frequency of testing is guided by employment-specific exposure characteristics, and “should be

determined by an occupational health nurse or other suitably qualified medical professional”.3

Testing blood lead levels if symptoms or history indicate lead poisoning is possible

Testing for raised blood lead levels can support a diagnosis of lead poisoning and should be requested if there is clinical

suspicion of lead poisoning based on the patient’s history and/or symptoms.

If blood lead levels are tested, also consider requesting:2

- Complete blood count – anaemia is common in patients with lead poisoning

- Renal and liver function testing – accumulated lead may adversely affect the function of these organs;

given that kidneys are the primary route for lead excretion, renal dysfunction may be a contributing factor to chronic

lead toxicity in some cases

Despite its importance in evaluating patients with suspected lead poisoning, clinicians should recognise that blood lead

testing is a measure of recent absorption and therefore reflects acute exposure events (i.e. within the past three to four

weeks).4 Lead stored in bone, teeth and organs which has accumulated over long periods of time will not be detected

with this approach.5 Testing is also unlikely to be completely diagnostic in isolation, particularly for neurodevelopmental

delays in children that can have a myriad of causes.4

There is no known safe level of lead exposure. Under the Health Act 1956 and the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms

Act 1996, cases of injury or disease caused by exposure to lead must be notified to a Medical Officer of Health, who will

subsequently assess the information about the exposure and determine if further follow-up is required.8 For lead

absorption, suspicion based on symptoms and history alone is insufficient for notification; a confirmed blood test is required

with the result meeting a certain threshold value.

On 9 April, 2021, the lead absorption notification level reduced

In 2007, the notifiable blood level for child or non-occupational adult lead absorption in New Zealand was lowered from

0.72 micromol/L to 0.48 micromol/L due to mounting evidence that lower blood lead concentrations were associated with an

unacceptable risk of adverse effects.6 On 9 April, 2021, the level at which blood lead absorption becomes notifiable

under the Health Act 1956 was reduced even further to 0.24 micromol/L (5 micrograms/dl).9, 10 This change is

consistent with the reference value recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States

and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.4

Why were the notification levels lowered further?

Recent findings from the multi-decade Dunedin Cohort Study suggest that the level of blood lead required to cause

irreversible neurological and behavioural affects is lower than previously thought.11, 12 Blood lead levels

were measured in study participants at age 11 years, and a variety of different endpoints were assessed throughout their

adult life.

Every 0.24 micromol/L increase in blood lead levels was found to be associated with:

- A statistically significant increase in psychopathology and neuroticism, as well as decreases in agreeableness and

conscientiousness up to age 38 years;12 this supports findings from other studies that have found adverse

behavioural effects associated with blood lead levels <0.48 micromol/L in children, e.g. impaired attention, increases

in impulsivity and hyperactivity.4

- A 1.19 cm2 smaller cortical surface area, a smaller hippocampal volume, lower global fractional anisotropy

and a BrainAGE index that is 0.77 years older at age 45 years, as revealed by MRI.11

- A 2.07-point lower IQ score and a 0.12-point higher informant-rated cognitive problem score at age 45 years.11

In addition, there is evidence that blood lead levels below 0.48 micromol/L increase the risk of hypertension in adults

and pregnant females, and may delay sexual maturity or puberty onset in adolescents.4 Recommendations on

a threshold below 0.24 micromol/L cannot be made as there is limited evidence of the effectiveness of public health

interventions below this level.

Clinicians can report notifiable lead absorption electronically

In general, notifiable lead exposure will be reported directly to a Medical Officer of Health by the community laboratory

performing the test. However, the information provided in these reports is limited. Clinicians in primary care are therefore

encouraged to also submit a Hazardous Substances Notification form to their Public Health Unit to provide additional information,

which can facilitate accurate identification of the exposure source, leading to controls being put in place to prevent further

public health issues. In addition, the Public Health Unit will submit notifications to the national Hazardous Substances

Surveillance System, with identifiable data removed, which:13

- Helps to further describe the epidemiology of lead exposure in New Zealand

- Informs policy development to improve monitoring and response strategies

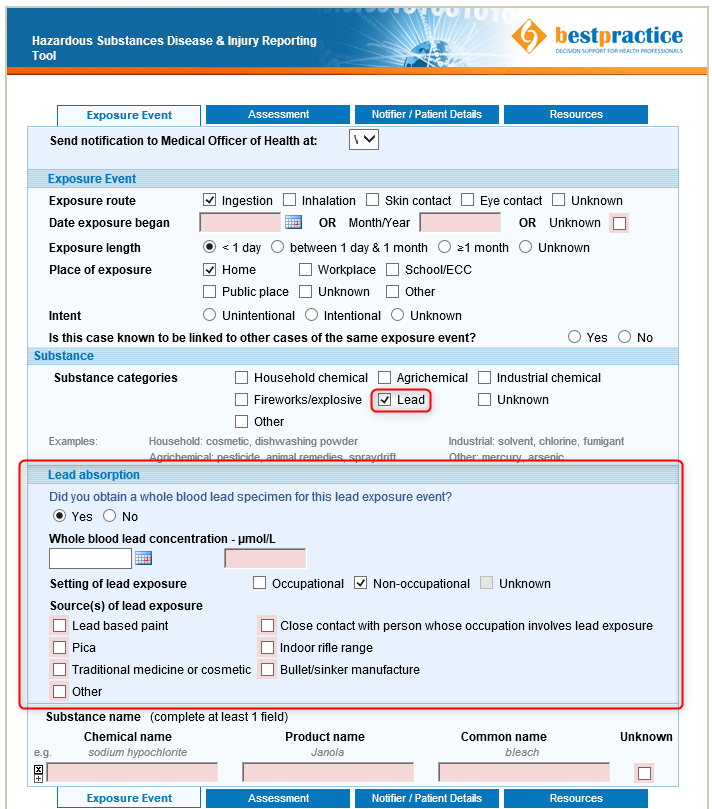

BPAC Clinical Solutions, in association with Environmental Health Intelligence New Zealand, and sponsored by the Ministry

of Health, have developed a Hazardous Substances Disease and Injury Reporting Tool (HSDIRT), that permits electronic reporting

of all hazardous substance exposures, including lead (Figure 1).13 It is available via Medtech,

Indici, MyPractice and Profile patient management systems.13

To access HSDIRT, go to the bestpractice Decision Support dashboard in your patient management system:

- Look for “Module List”

- Expand the “Hazardous Substances & Lead Notifications” tab

- Click on “Hazardous Subs & Lead Notifications” (N.B. ticking the green box will add the module to your “Favourites”)

If your practice does not have access to this tool and you want to make a notification, phone your Public Health Unit

directly. The staff will enter the case information into a HSDIRT notification form on your behalf.13 If the

patient is pregnant, their lead maternity carer should also be advised.

For a walkthrough video explaining how to access and complete HSDIRT notification

forms, see: https://vimeo.com/359445622

If you want the HSDIRT tool installed at your practice, contact BPAC Clinical Solutions:

Phone: 0800 633 236

Email: [email protected]

Website contact form: https://bpacsolutions.co.nz/contact/

For further information on hazardous substances disease and injury notifications,

see:

Figure 1. An example of reporting lead absorption through the Hazardous Substances

Disease & Injury Reporting Tool (HSDIRT; lead absorption section denoted in red box).

The Public Health Unit will provide advice on appropriate management and follow-up once a lead absorption notification

is received.4 In addition, they will direct remediation efforts to ensure that continued exposure to the source

of lead is prevented for non-occupational exposure, or contact WorkSafe New Zealand for work-related incidents.4

All patients should be provided with education about reducing the risk of future exposure regardless of their blood lead

level, i.e. avoiding the likely source(s).4 A follow-up blood lead level test should be scheduled (as advised

by the Public Health Unit) after the source of exposure has been remediated, and family members should be tested as appropriate

– particularly females who are pregnant and children aged under five years.4 If a decrease in blood lead levels

does not occur, the Public Health Unit should be contacted for further advice.

In rare instances, patients may have a very high blood level or severe symptoms that require immediate chelation treatment

in secondary care, e.g. with oral DMSA (dimercaptosuccinic acid). Chelation is usually only recommended for patients with

blood lead levels greater than 2.17 micromol/L.4, 5 The Public Health Unit will advise on the need for referral

to secondary care on a case-by-case basis, however, it is usually required:4

- In children or adolescents with blood lead levels greater than 0.72 micromol/L (paediatric advice or assessment)

- In pregnant females with blood lead levels greater than 2.17 micromol/L (acute obstetric assessment)

- In any adult with blood lead levels greater than 3.4 micromol/L (acute medical assessment)

For specific information on management, referral and follow-up in patients exposed to lead, see: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/environmental-case-management-lead-exposed-persons

For patient information on lead poisoning and reducing the risk of exposure, see: https://www.health.govt.nz/your-health/conditions-and-treatments/diseases-and-illnesses/lead-poisoning

Clinician’s Notepad: suspected lead poisoning

Assessment and diagnosis

- Review history

for possible exposure source or engagement in high-risk activities, the quantity of lead potentially consumed, and the

chronicity of exposure

- Evaluate whether

any other people may also have been exposed, e.g. family members (particularly children or pregnant females)

- Assess for

any current or historical gastrointestinal or neurological symptoms

- Request blood

lead level testing if there is clinical suspicion of lead poisoning, in addition to a complete blood count, renal and liver

function tests

Reporting

- If blood lead levels are ≥ 0.24 micromol/L, electronically report this to the Public Health Unit via the Hazardous Substances

Disease &

Injury Reporting Tool (HSDIRT) on your bestpractice Decision Support dashboard

- If this tool is not available, phone the Public Health Unit directly

Management

- As directed by the Public Health Unit. They will direct remediation efforts of the exposure source, and provide guidance

on:

- Repeat blood lead testing requirements for the individual; if levels do not decrease, contact the Public Health Unit

for further advice

- Whether additional blood lead testing is needed for family members

- Whether secondary care assessment is required (chelation treatment may be needed in rare cases for severe acute poisoning)