Key practice points:

- There is no evidence that opioids are effective for treating chronic non-malignant pain

- Opioids are associated with significant adverse effects, and analgesic efficacy decreases with continuous use due

to neuroadaptations that result in dependence, tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia

- Improving or retaining function should be the goal of treatment for most patients with chronic non-malignant pain;

regular use of potent opioids at high doses is contrary to this aim

- Pain is only one aspect of managing a patient with a chronic pain condition; attention to psychological and social

factors is essential, along with acknowledging and empathising with the emotional wellbeing of the patient

- If long-term use of opioids cannot be avoided, intermittent dosing using the lowest possible potency and dose is preferable

Opioids such as codeine, tramadol, morphine and oxycodone, continue to be frequently used in the management of chronic

non-malignant pain. However, there is a lack of evidence that they are effective when used long-term and should not be

considered an essential or routine component of management.

A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of treatments for chronic non-malignant pain found no significant difference

between opioids, non-opioids and non-pharmacological interventions for improving pain.1 This finding supports

an earlier meta-analysis and systematic review which found that opioids, including oxycodone, morphine, fentanyl, tramadol

and codeine, were associated with modest short-term analgesic benefits, but no evidence of effectiveness long-term.2,

3 A systematic review of treatments for chronic low back pain found low quality evidence for short-term efficacy

of opioids in terms of improvement in pain and function, but no differences between opioids, NSAIDs or antidepressants.

There was no evidence of long-term effectiveness and safety of opioids for treating low back pain.4

The long-term use of opioids is associated with multiple adverse effects, including: cognitive impairment, respiratory

depression (including fatal opioid-induced ventilatory impairment), sleep apnoea, increased risk of falls and fall-related

injuries, somnolence, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, loss of ability to feel pleasure (anhedonia), depression, hypotension,

bradycardia, vasodilation, constipation, nausea, delayed gastric emptying and effects on the immune system.5, 6 Using

opioids long-term can also have negative effects on relationships and social function and affect ability to work and perform

other functions.6

Opioids have significant medicine interactions that can pose risks to patients, such as additive sedation and other

CNS effects. Harm is increased in older people with multiple co-morbidities, and when opioids are taken concurrently with

other sedating medicines or substances, e.g. benzodiazepines, gabapentin and alcohol.7

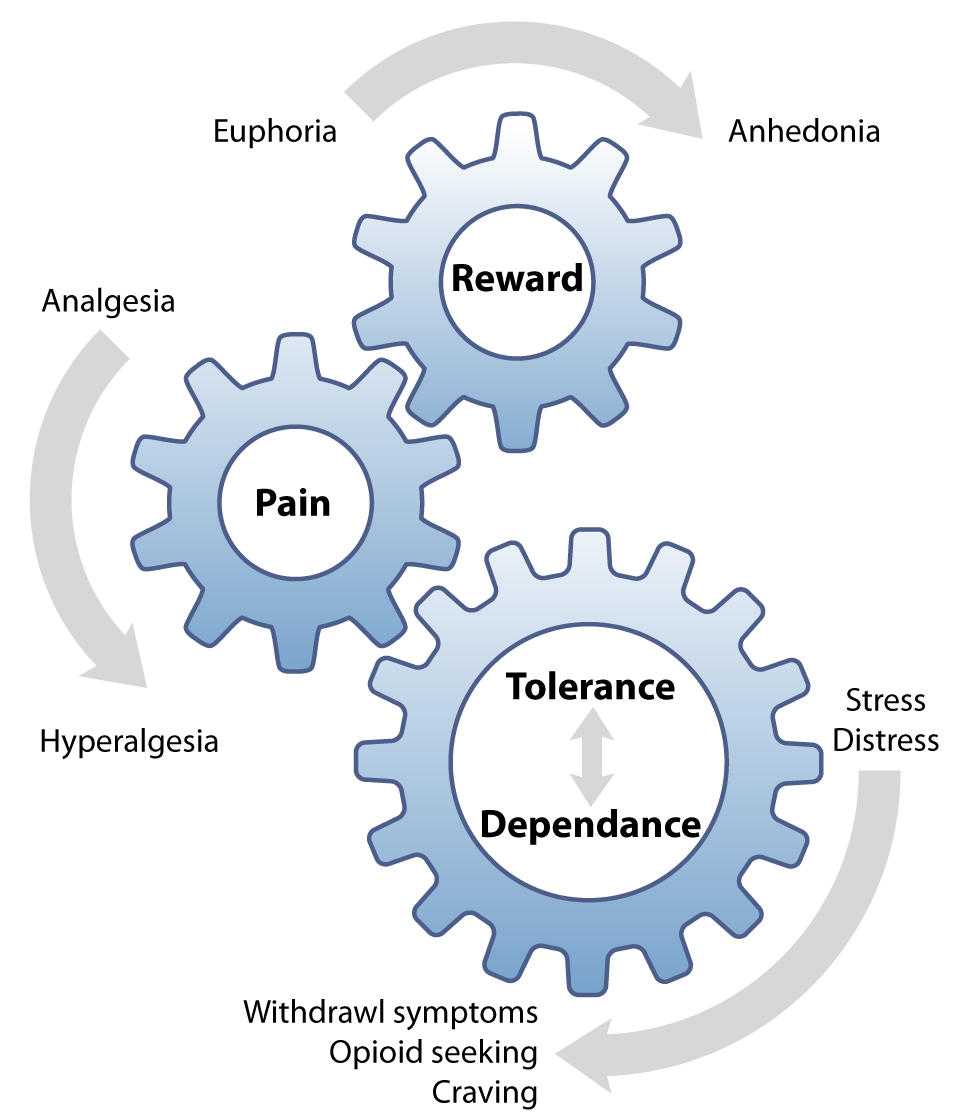

Tolerance, dependence and hyperalgesia

When opioids are prescribed continuously, tolerance and dependence occur due to neuroadaptations.6 Opioid

tolerance is the need to take increasingly higher doses to achieve the same level of analgesia, and may occur within one

or two weeks of beginning treatment.6 Opioid dependence is a state of neuroadaptation evidenced by acquired

tolerance and physical symptoms of withdrawal if the next dose of opioid is not received or the level of opioid is abruptly

reduced. Symptoms of withdrawal include agitation, nausea, diarrhoea, dilated pupils, increased pain (withdrawal hyperalgesia)

and anhedonia.6 In chronic pain, it is likely that withdrawal hyperalgesia and anhedonia drive the need for

continued opioid use.6

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia is an increased sensitivity to pain that occurs with prolonged use of opioids. Pain actually

increases while taking opioids, and it is often unrelated to the original cause of the pain and has different characteristics.8

Dependence, tolerance and hyperalgesia prevent patients from gaining satisfactory pain relief from opioids (Figure 1).6 This

is why many patients who take opioids long-term report that their pain is still intense despite high doses. It would seem

logical that an opioid is required to prevent their pain from being even worse, yet what can be difficult for patients

to comprehend is that taking the opioid caused this problem in the first place.6 Doses are escalated to meet

analgesic requirements, but then the patient also becomes tolerant to this dose and the cycle repeats until the patient

is taking the maximum dose, and this still does not provide adequate analgesia.6

“If we put people into a state of continuous withdrawal, we do not help their pain, we compromise safety,

and we change their motivations and beliefs”. 6

Figure 1: The tolerance and dependence cycle of long-term opioid use. When opioids are

used continuously, each dose is needed to prevent dysphoria, rather than inducing euphoria.6

Psychological factors significantly influence the experience of pain and ability to tolerate it. Often the primary cause

for decreased quality of life and disability in people with chronic pain is altered mood, e.g. feelings of hopelessness,

helplessness and depression, rather than the pain itself.6 When a person experiences pain long term, their

brain restructures and reorganises pain responses and pain perception shifts from the sensory areas of the brain to the

emotional areas.6 “Pain catastrophising” is common among people with chronic pain. This is repeated negative

thoughts during actual or anticipated pain, and it can compromise the success of any treatment plan.9

The key to managing pain is to understand and empathise with the patient’s experience, and acknowledge that they have

pain and their life has been significantly changed by this.10 With the patient, find a method that allows

them to be less affected by their pain and therefore better able to cope. Shift the focus of conversations from improving

a pain score, to improving function and health-related quality of life, e.g. rather than asking the patient how intense

their pain is, ask them what activities they are able to achieve.6

Ways to help patients cope with their pain include:10

- Help them to recognise the type, intensity and duration of pain they are feeling and how this can vary throughout

the day and between days so they have a better understanding of what to expect

- Redefine a “new normal” that reinforces positive aspects of life and future plans, rather than focusing on the

losses which the pain has caused

- Encourage participation in a group and sharing pain experiences with others

- Set realistic and achievable functional goals based on their own expectations, not those of their family or friends

- Understand that there may be no cure for their pain and that managing their pain and improving function are the

goals

- Be part of treatment decisions and experiment with different methods of managing their pain (see: “Options

for managing chronic non-malignant pain”)

Further information:

Patient information about managing chronic pain is available from:

Health Navigator - Chronic Pain or Retrain Pain Foundation

Many patients with chronic pain will expect to be treated with an opioid and believe that it is the only thing that

will “fix” their pain. The challenge is in getting patients to accept that opioids are not the centre of the treatment

plan. This relies on effectively communicating why opioids are not the best treatment for many chronic pain conditions,

explaining the adverse effects associated with opioids, and then being able to offer an acceptable management plan.

A multi-modal treatment approach is recommended. The effectiveness and best combination of treatments is individual

to each patient. Most patients with chronic non-malignant pain will be able to be managed in primary care, but discussion

with or referral to a specialist pain clinic may be required in some cases, e.g. if multiple treatment approaches have

been unsuccessful.

Non-pharmacological treatments are recommended for all patients, including:

- Exercise, general physical activity, pilates, yoga, Tai Chi

- Massage

- Acupuncture and nerve stimulation techniques (TENS)

- Cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness, meditation, relaxation

- Activity pacing techniques, i.e. arranging activities into manageable portions of time

- Heat or cold therapy

- Participation in social activities, special interest groups, listening to music, general distraction techniques

Pharmacological treatments are used only if indicated for the type of pain the patient has and if use of the medicine

for this condition is supported by evidence. Options may include:

- Paracetamol

- NSAIDs, e.g. ibuprofen, naproxen, celecoxib

- Topical NSAIDs, capsaicin

- Tricyclic antidepressants, e.g. amitriptyline, nortriptyline

- SSRIs, e.g. if co-existing depression

- Gabapentin or pregabalin: caution with these medicines due to risk of dependence and misuse

- Secondary care treatment options such as permanent nerve blocks, epidural steroid injections, spinal cord stimulation

- Consider referral to other health providers, including:

- Occupational therapist, e.g. for assistance with work-related postural problems or repetitive strain

- Physiotherapist, chiropractor or osteopath, e.g. for massage, manipulation, mobilisation, strapping

- Maori health provider, e.g. for a cultural and spiritual perspective to treatment, Rongoā (traditional plant-based

healing)

- Multidisciplinary pain clinic, e.g.

TBIhealth: Pain Management Service

Further information:

For further information about each of these treatments, including evidence statements, and for an overview of CBT techniques

for chronic pain, see:

Helping patients cope with chronic non-malignant pain: its not about opioids bpacnz, September 2014

Patient information on mindfulness is available from:

Health Navigator: How mindfulness supports wellbeing

Using opioids to treat chronic pain should be regarded as the exception rather than the rule, and only when all other

treatment options have been trialled.6 If opioids are used, protocols should be put in place to minimise the risk of

harm, see: “Unintentional misuse of prescription medicines”, bpacnz , 2018.

Neither the acute pain model of prescribing opioids at a potency related to the severity of pain, then de-escalating

treatment as pain improves, nor the palliative care model of maximising opioid analgesia to enhance comfort in a patient

with limited function apply to the management of chronic, non-malignant pain. Opioids should be used at the lowest effective

potency and dose, e.g. do not use morphine if pain can be managed acceptably with codeine, and for the shortest possible

time. Pain-contingent, “as needed”, dosing is strongly preferable to regular, “by the clock” dosing.

Intermittent dosing of opioids is preferable to continuous use

There is evidence that lower dose and/or intermittent use of opioids reduces the risks of treatment without compromising

benefit.11 It is thought that the neuroadaptations associated with continuous use of opioids are less likely

to occur if opioids are used intermittently or occasionally.6

In a survey of 1781 patients in the United States using opioids for chronic non-malignant pain, those who reported time-scheduled

dosing used substantially higher doses of opioids and had a greater level of concern about their opioid use than those

who used pain-contingent dosing.12 The patients using time-scheduled dosing were more likely to report being

preoccupied with opioid use, being less able to control their opioid use and more worried about opioid dependence. Reported

pain intensity between the two groups was similar.12 Findings from the Middle-Aged/Seniors Chronic Opioid

Therapy (MASCOT) study revealed that patients who used opioids minimally or not at all for chronic non-malignant pain

had better pain intensity and activity interference (i.e. impaired function) outcomes than those who used opioids regularly.11 There

was no difference in pain intensity or functional outcomes between patients who used opioids at low doses or intermittently

compared to those who used opioids at high doses or regularly.11