Update 2022:

New data suggests that topiramate is associated with an increased risk

of neurodevelopmental disorders of the same magnitude, or higher, than sodium valproate

The 2022 Nordic register-based study of antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy (SCAN-AED) is a large observational study that included 4,494,926 children born between 1996 and 2007; 24,825 children were exposed to anti-epileptic medicines during gestation and of these, 16,170 were born to mothers with epilepsy. In children whose mothers had epilepsy but were not taking anti-epileptic medicines during pregnancy, there was a baseline eight-year cumulative incidence of 1.5% for autism spectrum disorder and 0.8% for intellectual disability. For children of mothers taking topiramate or valproate, the eight-year cumulative incidence for autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability was 4.3% and 3.1%, and 2.7% and 2.4%, respectively. The use of topiramate was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.8 (95% CI, 1.4 - 5.7) for autism spectrum disorder and 3.5 (95% CI, 1.4 - 8.6) for intellectual disability. Higher doses of topiramate were associated with a further increased risk. These results suggest a strong association between the use of topiramate during pregnancy and neurodevelopmental disorders in the child.

Until now, there has been a lack of data to fully assess the magnitude of risk with topiramate compared to other anti-epileptics, but this new evidence suggests that topiramate poses a similar risk of neurodevelopmental adverse effects as sodium valproate (or potentially higher) therefore the same level of caution when considering use of topiramate in females of child-bearing potential should be applied.

Bjørk M-H, Zoega H, Leinonen MK, et al. Association of prenatal exposure to antiseizure medication with risk of autism and intellectual disability. JAMA Neurol 2022;79:672. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.1269

Antiepileptic medicines, also known as anticonvulsants, are a first-line pharmacological treatment for seizure control

in people with epilepsy. They are also an option for symptom management in some mood disorders, e.g. bipolar disorder,

neuropathic pain and for migraine prophylaxis. The potential benefits of using antiepileptic medicines can vary widely

depending on the indication and individual response to treatment. The risks, however, are the same; antiepileptic medicines

are associated with an increased risk of teratogenic effects when used during pregnancy (see below).

It is recommended that antiepileptic medicines are only used when essential, and at the lowest effective dose. Sodium

valproate should not be initiated in women of child-bearing age for focal epilepsy, pain, headache or psychiatric illness unless

there are no other treatment options available and the benefits and risks have been considered.1, 2

In epilepsy, the use of antiepileptic medicines is almost always essential, including during pregnancy.3 Sodium

valproate is usually regarded as the most effective antiepileptic medicine for generalised epilepsy; however, due to its

higher teratogenic risk (see later), levetiracetam or lamotrigine should be trialled first-line in women of child-bearing

age – although sodium valproate may ultimately be required to achieve seizure control. Sodium valproate is not generally

considered first line treatment for focal epilepsy – lamotrigine and carbamazepine are preferred, with levetiracetam a

second line alternative.

In bipolar disorder, lithium, olanzapine, quetiapine and fluoxetine are typically first-line options,

along with non-pharmacological interventions. If patients do not respond sufficiently to these medicines, sodium valproate

or lamotrigine may be trialled.4

In neuropathic pain, tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin or pregabalin are considered equally effective

first-line pharmacological treatment options. Topical capsaicin cream can be used for localised pain. Carbamazepine is

the first-line treatment for trigeminal neuralgia.5

In migraine, people who are unable to effectively control symptoms during acute attacks may consider

using prophylactic medicines. Typically, prophylactic treatment is only required for a short time period. Beta-blockers

(nadolol or metoprolol) are first-line options, amitriptyline is an alternative. Nortriptyline, venlafaxine or propranolol

(not if using rizatriptan) can also be trialled. Topiramate or sodium valproate are “last resort” options if all other

treatments are ineffective.6

For further information, see

Antiepileptic medicines have adverse effects on fetal development

The use of antiepileptic medicines during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations,

lower intelligence quotient (IQ) scores and higher need for educational intervention in the affected children.1 The

combination of these adverse effects has been referred to as Fetal Anti-Convulsant Syndrome (FACS).1

In pregnancies where a woman has taken an antiepileptic medicine, rates of major congenital malformations are 4–7% compared

to 2–3% in the general population.1 However, rates vary according to the antiepileptic medicine(s) used and

dose. Most of the available data on teratogenicity comes from females taking antiepileptic medicines for epilepsy, but

the risks are thought to be similar when used for other conditions, such as bipolar disorder.7

There is no evidence that antiepileptic medicines are associated with specific malformations. Major and minor congenital

malformations* may affect almost any body system, including cardiac, renal, urinary, gastrointestinal, skeletal

and neural tube defects, and facial dysmorphisms.8

The use of antiepileptic medicines during pregnancy may also increase the risk of obstetric complications such as spontaneous

abortion or a child being born small for gestational age.9–11

* Major congenital malformations are those that have significant medical, social or cosmetic

consequences, such as atrial or ventricular septal defects, dysplastic hip or hypospadias. Minor congenital malformations

are defined as a structural anomaly or dysmorphic feature which does not require surgical intervention or treatment, such

as epicanthal folds, hypertelorism (widely spaced eyes), microstomia (small mouth), or a broad or flat nose.8, 12

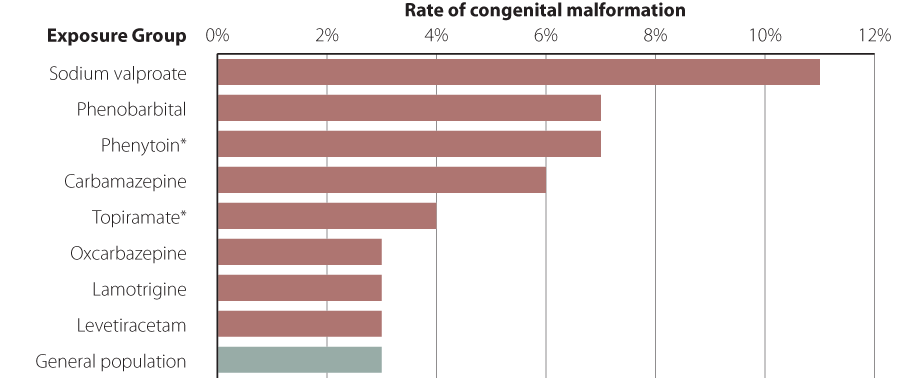

Sodium valproate is associated with the highest risk

The risk of congenital malformations is highest with the use of sodium valproate, where approximately 10–11% of pregnancies

are affected, followed by phenobarbital, phenytoin and carbamazepine (Figure 1).1, 8 Available

data do not provide sufficient information to estimate risk for all available antiepileptic medicines, such as topiramate,

lacosamide, gabapentin or pregabalin.13 Low rates of congenital malformations have been reported for lamotrigine

and levetiracetam.1, 8 However, this does not necessarily mean that there is no risk from using these medicines

during pregnancy.

Figure 1: Rates of major congenital malformations associated with antiepileptic medicine use1, 8 N.B. this data does not

include neurodevelopmental adverse effects in affected children.

* Data on risks associated with phenytoin or topiramate use are based on limited numbers of pregnancies

Multiple medicines are associated with higher risk

A meta-analysis reported a rate of congenital malformations of 17% when more than one antiepileptic medicine was taken

during pregnancy.13

Higher doses are associated with higher risk

Higher doses are associated with higher rates of congenital malformations for a number of antiepileptic medicines, including

sodium valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine and phenobarbital.8 For example, congenital malformations occur

in approximately 6% of pregnancies when less than 650 mg/day of sodium valproate is taken, compared to over 25% of pregnancies

when more than 1450 mg/day is taken.14 Typical maintenance doses of sodium valproate for the treatment of epilepsy

are 1000–2000 mg, daily.15

Sodium valproate is also associated with neurodevelopmental effects

Exposure to sodium valproate during pregnancy can have adverse outcomes on a child’s intelligence and educational achievement.

Children who are exposed to sodium valproate during pregnancy have on average IQ scores 8–11 points lower and inferior

language skills compared to children who are not exposed, and may have increased risks of autism spectrum disorder and

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.1, 16, 17 There are currently less data available regarding the neurodevelopmental

effects of antiepileptic medicines other than sodium valproate. However, reduced intelligence and lower educational achievement

has been reported in children exposed to multiple antiepileptic medicines taken concurrently during pregnancy.13,17

Although antiepileptic medicines are often initiated in secondary care, or prescribed on the recommendation of a clinician

in secondary care, dispensing data show that the majority of prescriptions are subsequently written by a general practitioner.18 Clinicians

in primary care are therefore well-placed to discuss the potential benefits and adverse effects of antiepileptic medicines

with patients.

Women of child-bearing age who are prescribed an antiepileptic medicine (or being considered for treatment) should be:19

- Informed of the risks of seizures during pregnancy

- Informed of the potential teratogenic effects of antiepileptic medicines

- Involved in discussions regarding lower risk or alternative treatment options, if clinically appropriate

- Provided with appropriate contraception

- Encouraged to plan a pregnancy in advance

Start discussions about benefits and risks early

Women of childbearing age, and their caregivers if appropriate (e.g. if the patient is a child), need to be well-informed

about the risks associated with antiepileptic medicine use during pregnancy and the need for contraception, before they

initiate these medicines and before they become sexually active. Clinicians should revisit these issues with young patients

as they mature.

Balance the risk: It is also important to discuss the risks associated with not taking antiepileptic

medicines and the need for patients to keep taking their medicines if they become pregnant. Reassure patients and caregivers

that despite increases in risk, the majority of children exposed to sodium valproate or other antiepileptic medicines

do not have congenital malformations.3

Patients, caregivers and clinicians can take away different impressions of what is discussed during a clinical encounter.

Check the understanding of the conversation at the end of the consultation.

Prescribe appropriate contraception

It is essential that women of childbearing age who are taking an antiepileptic medicine are also taking appropriate

contraception. The risks of congenital malformations associated with antiepileptic medicine use during pregnancy are highest

in the first trimester, before many people realise they are pregnant.1

Ideally, women taking an antiepileptic medicine should be prescribed two forms of recommended contraception, i.e. one

of the options in Table 1 plus condoms, taking into account the potential for medicines interactions

with enzyme-inducing antiepileptic medicines (Table 2).1, 20 If women are prescribed an

oral contraceptive, ensure they know what to do if a dose is missed (especially important if taking progesterone-only

pills) or if vomiting or diarrhoea occurs.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives are the most effective form of contraception. This includes intrauterine

devices and progestogen implants (if not using an enzyme-inducing antiepileptic medicine), with less than 1% of women

experiencing pregnancy after one year of use (Table 1).21, 22

Medroxyprogesterone acetate injections, progesterone-only or combined hormonal pills have low rates of failure in circumstances

of perfect use, however, with typical use 6-9% of women experience an unintended pregnancy after one year.21, 22

Patient information leaflets covering various contraceptive options are available from:

The New Zealand Formulary Patient Information Leaflets Index

Contraceptive options for women taking enzyme-inducing antiepileptic medicines

The use of combined hormonal contraceptives or progesterone-only pills or implants is not recommended within 28 days

of taking an enzyme-inducing antiepileptic medicine (Table 2).13 Some clinicians may be

familiar with the practice of using a high-dose hormonal contraceptive, e.g. 50 micrograms of ethinylestradiol, in patients

taking an enzyme-inducing antiepileptic medicine with the purpose of counteracting the change in hepatic metabolism.23 However,

the contraceptive effectiveness of this method has not been studied.13 A wider variety of contraceptive options

are now available, making it easier to avoid this combination of medicines. For patients taking lamotrigine, the use of

combined hormonal contraceptives is not recommended as these medicines reduce circulating levels of lamotrigine and can

lead to an increase in seizures.13

Emergency contraception options

A copper IUD is recommended for emergency contraception for women taking enzyme-inducing antiepileptic medicines.13,

20 Alternatively, levonorgestrel 3 mg (two tablets) can be prescribed, however, this is an unapproved dose and

the effectiveness of this option has not been adequately studied.15, 20

Standard emergency contraceptive options can be used for patients taking other antiepileptic medicines.20

Some patients experience nausea after taking an oral levonorgestrel emergency contraceptive; if vomiting occurs within

three hours a repeat dose is recommended.20

Table 2: Antiepileptic medicines and their effects on hepatic enzymes20, 24, 25

| Enzyme-inducing antiepileptic medicines |

Non-enzyme-inducing antiepileptic medicines |

- Carbamazepine

- Oxcarbazepine

- Phenobarbital

- Phenytoin

- Primidone

- Rufinamide

- Topiramate

|

- Clobazam

- Clonazepam

- Ethosuximide

- Gabapentin

- Lacosamide

- Lamotrigine

- Levetiracetam

- Pregabalin

- Retigabine

- Sodium valproate

- Vigabatrin

|

Further information on contraceptive interactions with antiepileptics is available from

Combined oral contraceptives: Issues for current users bpacnz, April 2008

Plan before a pregnancy

For women with epilepsy, planning prior to pregnancy is especially important to manage the combined risks of pregnancy,

their epilepsy and the antiepileptic medicines used to control seizures. Approximately one-third of women with epilepsy

have an increased frequency of seizures during pregnancy.13 Seizures during pregnancy are a serious complication

and carry mortality risks for both the mother and unborn child, including changes in fetal heart rate, reduced birth weight,

pre-term birth and pregnancy loss.3, 26 Uncontrolled seizures are also a risk factor for sudden unexpected

death in epilepsy (SUDEP).13

Women with epilepsy should be encouraged to discuss pregnancy plans at least six to twelve months in advance so that

treatment can be altered as necessary to establish good seizure control with a medicine regimen which has the lowest possible

risk of harm to the fetus.1, 3 Pregnancy planning in women with epilepsy results in improved seizure control

during pregnancy, fewer pregnancies exposed to sodium valproate and fewer changes in antiepileptic medicine regimen during

pregnancy.27 Obstetric care is necessary for women with epilepsy who become pregnant. Planning prior to pregnancy

is also important for women regularly taking antiepileptic medicines for indications other than epilepsy.

If pregnancy occurs without prior planning, urgent referral to or discussion with the patient’s neurologist or psychiatrist,

and an obstetrician is recommended; ideally within 48 hours of the pregnancy being confirmed.1 Advise patients

not to stop taking their medicines of their own accord as this may cause frequent and prolonged seizures which places

their unborn child and themselves at risk.

A higher folic acid dose is recommended for females taking antiepileptic medicines

Folic acid supplementation is recommended from a minimum of four weeks before to at least 12 weeks after conception

to reduce the risk of neural tube defects. A higher than usual dose of folic acid (5 mg per day) is recommended for females

taking antiepileptic medicines.28 Folic acid supplementation reduces the background risk of spontaneous neural

tube defects, however, it does not reduce the teratogenic effects of antiepileptic medicines.1, 13

Further resources

Further resources

The Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC), Ministry of Health, Health Quality & Safety Commission and Foetal Anti-Convulsant

Syndrome New Zealand have developed booklets for healthcare professionals and patients regarding the risks associated

with the use of antiepileptic medicines to aid discussions with patients about how to mitigate these risks. PDFs of these

booklets can be downloaded from the web addresses below, or contact [email protected] to order printed copies.