Axial spondyloarthritis (axial SpA) - an uncommon cause of a common symptom

Key practice points

- Axial SpA is an umbrella term for a group of inflammatory conditions that primarily affect the spine and sacroiliac

joints. There are two main subtypes that exist on a continuum of disease:

- Non-radiographic axial SpA – where inflammation is affecting soft tissue, causing pain, but

has yet not caused direct damage to the axial joints; and

- Ankylosing spondyloarthritis – where there are significant radiographic abnormalities in the

axial joints

- Despite differences in radiographic features between these subtypes, the symptoms, signs and disability experienced

by patients can be the same, and the radiographic distinction does not change the initial approach to management

- Chronic low back pain is a common presenting feature in primary care; however, axial SpA is likely to be the

cause in a very small number of these patients – it affects less than 1% of the population overall

- Distinguishing features that should increase suspicion of an inflammatory cause of back pain include: family

history (particularly if other family members have been diagnosed with an HLA-B27-related condition,

e.g. inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] or psoriatic arthritis), younger age of onset, raised CRP, nocturnal pain, morning stiffness lasting >30

minutes, improvement with exercise and response to NSAIDs

- Important differential diagnoses of chronic back pain to consider based on the patient’s history include physical

conditions such as muscle pain, fracture, herniated disc, spinal stenosis, as well as biopsychosocial factors

that may contribute to the perception of pain

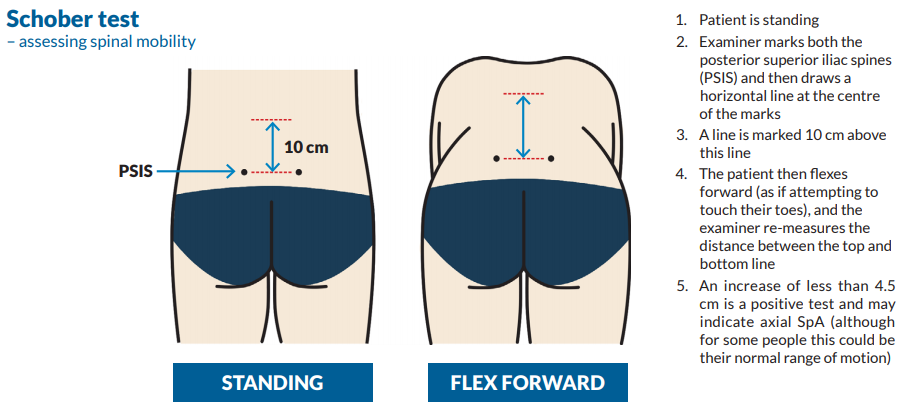

- The sacroiliac joint stress test (Figure 1) and the Schober test (Figure

2) are useful approaches to assess

the patient's pain localisation and spinal mobility, respectively; the physical assessment should also look for

features of systemic or extra-articular conditions, as these are often present, e.g. enthesitis, peripheral arthritis,

dactylitis, uveitis, psoriasis, IBD

- Laboratory testing typically includes CRP and HLA-B27 genetic testing; stool culture and chlamydia

PCR may be considered if reactive arthritis is a possible differential diagnosis, or testing for autoantibodies

may be useful if there is suspicion of other rheumatic conditions

- Imaging can be informative, but this is usually co-ordinated in secondary care

- If there is a high clinical suspicion of axial SpA, the patient should be referred to a rheumatologist who

will confirm the diagnosis, establish a treatment plan, and inform on subsequent monitoring requirements (e.g.

disease activity scoring with a tool such as BASDAI, medicine-specific monitoring, cardiovascular risk assessment)

- A NSAID should be prescribed while awaiting a rheumatology appointment, e.g. naproxen; when used alongside

regular exercise and other lifestyle interventions, NSAIDs are effective for controlling disease activity and

improving the quality of life in many patients

- Biologics, e.g. TNF-inhibitors, may be considered in a limited number of patients if at least two different

NSAIDs have been trialled and are ineffective

- Although the disease course is highly variable for patients with axial SpA, early treatment is associated with

better outcomes, e.g. reduced skeletal damage and maintenance of mobility

Figure 1. The sacroiliac joint stress test.

Figure 2. The Schober test.

Abbreviations: BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; HLA-B27,

human leukocyte antigen B27; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.